1. Introduction & Key Recommendations

In this study, we designed and tested new messages for animal advocates based on findings from previous research. In particular, our goal was to develop new counter-narratives that have the potential to displace the dominant narratives around farming animals, which justify it.

We chose to focus on narrative in particular because narratives can deliver specific benefits. Research has shown that compared to purely informational messaging, narrative has a greater potential to grab people’s attention, create emotional connections, and help people remember complex ideas.

We used focus groups in order to mimic the way that people often process new ideas through conversations with peers, rather than in isolation. In a group setting, participants could hear each other’s arguments for and against the messages we were testing and we could see which arguments would win out in the group as a whole.

Among many elements of messaging strategy, this research mainly focused on emotional register (tone), messengers, and the message itself. These are our top recommendations:

- The evolving together frame and the evolution metaphor are a great starting place for persuasive messages, but specific policy proposals still face many hurdles to public acceptance, especially concerning the affordability of animal-free food.

- The meat-eating messenger: For messages involving emotion, the most important quality for messengers is not authority but relatability and trustworthiness. The most relatable and trustworthy messengers we tested were ordinary Americans who explicitly mentioned that they still eat meat, especially from demographics not usually associated with veganism (men, people of color, working-class people, and older people).

- Advocates must strike a balance when including emotional appeals in their messages. Many people say they prefer messages focused on facts, especially when citations are provided. While creating an emotional connection with the issue is often a necessary first step, messages with an elevated emotional tone risk being dismissed as hysterical or over-the-top. Advocates can use toned-down emotional appeals and let images do the heavy emotional lifting. We can also explicitly make the case that an emotional response to animal abuse is sane and healthy (though still without the use of emotionally elevated language).

- Tell stories of ordinary meat-eaters experiencing a shift in perspective away from the consumer frame and embracing the goals of the animal movement.

- Target the humane deception and assert that it is “no secret” that welfare labels are nothing but a marketing ploy.

- Consider the other new counter-narratives recommended in this report as well as our proposed modifications to narratives already in use.

- Use the radical flank effect: campaigning for highly ambitious policy demands makes other policies more palatable. Moderate factions should highlight policies meant to make animal-free foods more affordable and accessible. Meanwhile, in order to activate radical flank effects around political viability, radical factions should focus on pressing for ambitious policies (such as meat bans) through credible pathways. Merely calling for such an outcome may not suffice; the public should believe that such measures are being seriously and credibly pursued.

2. Primary Questions & Research Design

What messaging strategies are most effective for overcoming the dominant narratives in favor of using animals for food and building support for government intervention to accelerate the transition away from animal agriculture? The two primary components of messaging strategy we focused on were the narrative represented and the characteristics of the messenger, the person delivering the message. We also experimented with imagery.

Using one-on-one interviews, we had previously identified several patterns in how ordinary meat-eaters relate to the issue of using animals for food. From that research stage to this one, we made two pivots. First, we switched from interviewing one participant at a time to group interviews of 2-5 strangers. The primary reason for this is that people do not process social and political questions alone but as members of a group. Focus groups are thus a research strategy to mimic the social arena where animal advocates’ messages are heard and discussed.

The second significant change was from asking open-ended questions to testing written messages. While one-on-one advocacy is uniquely useful, a great deal of advocate messaging to the mass public is in the form of videos, ads, and other one-way communications. In this context, advocates can’t alter their message based on the audience's response; we only have one chance to get it right. Accordingly, for this research, we limited ourselves to presenting static messages and did not attempt to refute the counter-arguments of participants.

What criteria did we use to assess the efficacy of each message? This had to do with our organizing the public into base, opposition, and persuadable middle categories. No message will have the same effect on everyone. Simply put, we were looking for a message which could catch on among the base, overcome resistance in the persuadables, and in doing so, isolate the opposition.

The base, representing the most sympathetic 20% or so of the public, are the people we hope will adopt and spread a reframing of the issue. Thus, a strong candidate narrative is one that these people can easily remember and adopt, and that inspires and motivates them. We were interested in which messages people would refer back to later in the interview or borrow language from. To be clear, we are not suggesting that 20% of people will take an active role in the animal movement; the movement should aim to convert these people into passive supporters, who do little more than speak using the movement’s narrative.

A strong narrative should also win the support of a majority of the public. Our goal for the persuadable middle is not necessarily that they will actively adopt the new narrative any time soon but that hearing it can move them closer to us. We don’t need to turn 51% of people into advocates; we just need them to vote in favor of pro-animal laws, however begrudgingly.

That said, we did not necessarily expect to find a narrative that could convert 50% of people to support the movement just from hearing it in one focus group. If such a strong message existed, we wouldn’t need a social movement. For instance, if someone had run a study like this ten years ago on racialized police violence, the “Black Lives Matter” narrative likely would have fallen flat. New narratives alone are sterile; their success depends on a strategy for winning narrative dominance. Thus we were mainly seeking a crack in the armor of the dominant narrative, a counter-narrative showing enough promise that it could, with the help of a sustained social movement, catch on among the base and cause a shift in perspective among the majority.

2.1 Methods

We conducted 40 focus groups with 130 participants in total. Participants were paid $40 each for a 90-minute session. Methods were similar to the individual interviews described in the previous report in this series, except for the differences below.

We began intentionally excluding conservatives from the study. Our findings in individual interviews corroborated substantial evidence that conservatives are generally more hostile to animal freedom messaging. We expected to meet greater resistance to reframing the issue in group interviews compared to individual interviews and felt that including conservatives in the study would result in such high resistance to all messages that relatively strong messages would be difficult to notice. However, due to participants’ misreporting on the initial intake form combined with our own errors, we wound up with 13% conservative participants.

After an off-topic icebreaker question, each focus group started with the interviewer presenting a stimulus. For roughly the first 20 focus groups, the stimulus was one of six variations of a fictional news article about a ballot measure introduced in either Colorado or Oregon, featuring quotes from advocates and opponents (participants were informed of the deception after the interview was over). The nature of the measure varied, from banning slaughterhouses or the sale of meat to subsidizing meat alternatives. Participants read the stimulus out loud before discussing their reactions.

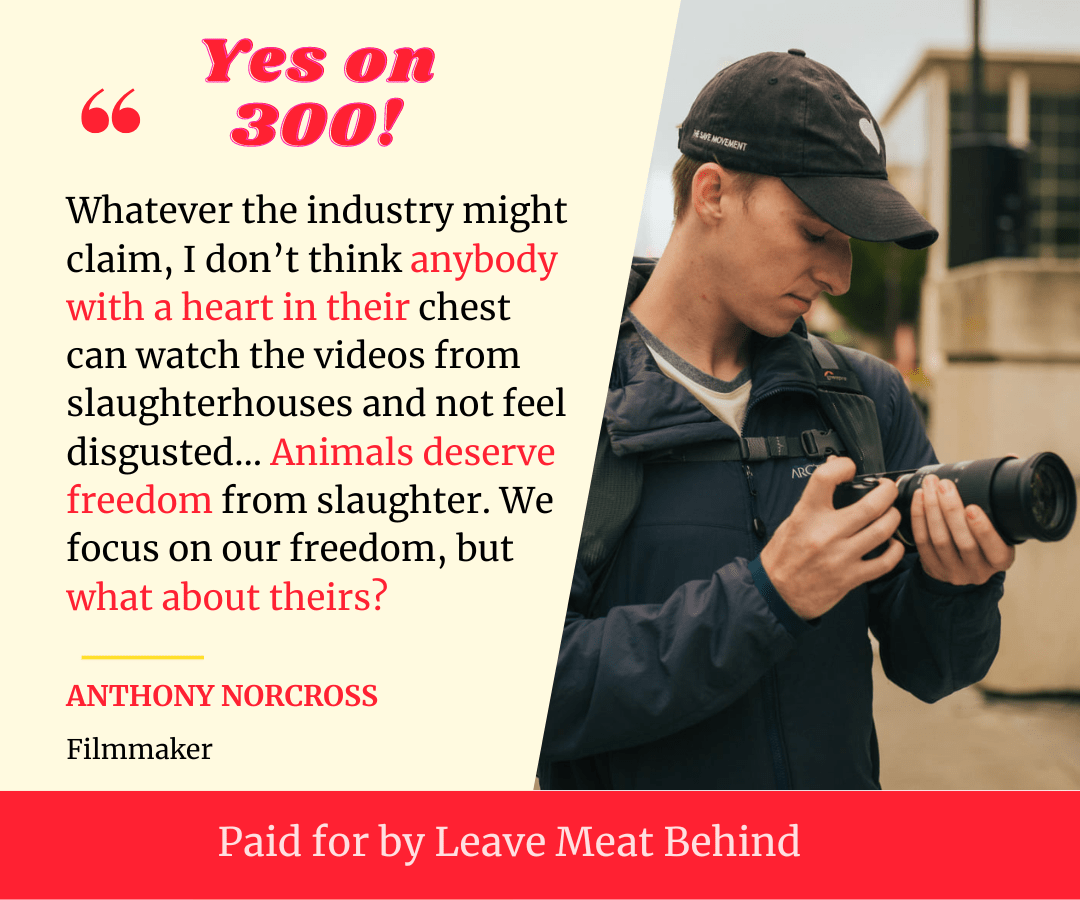

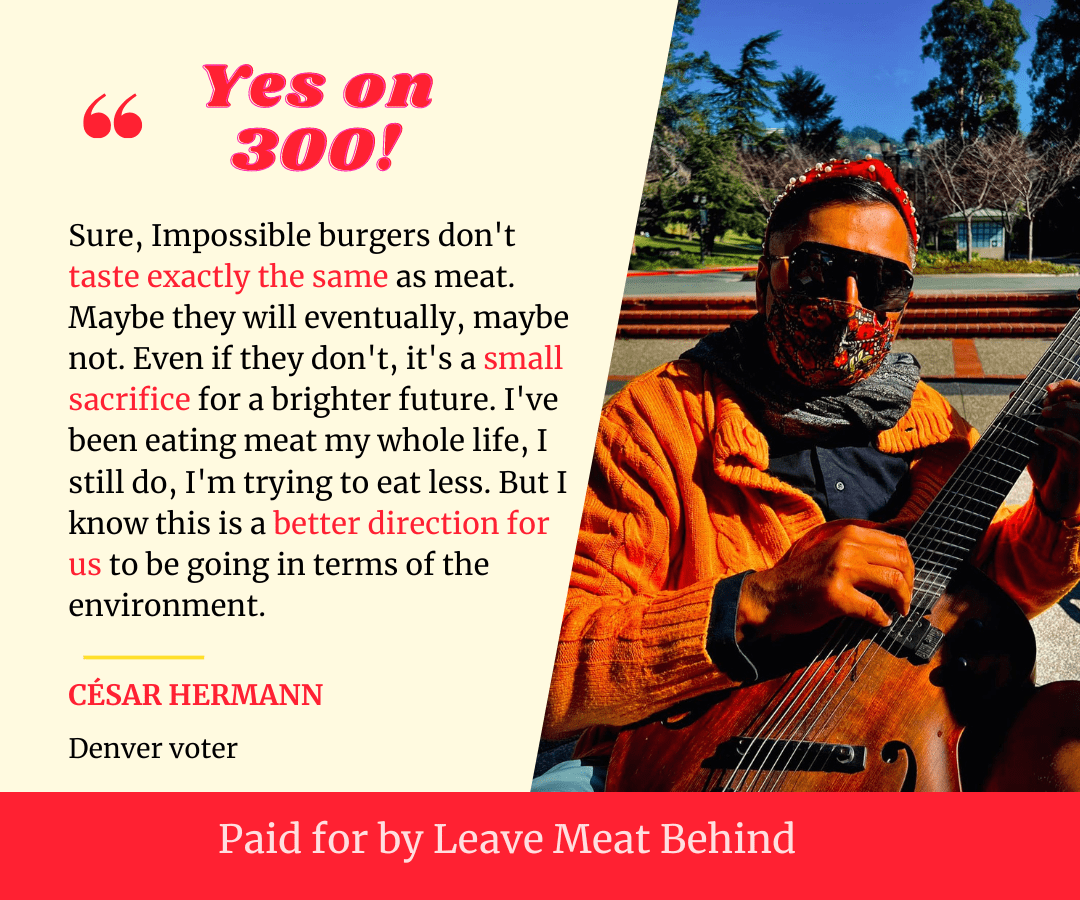

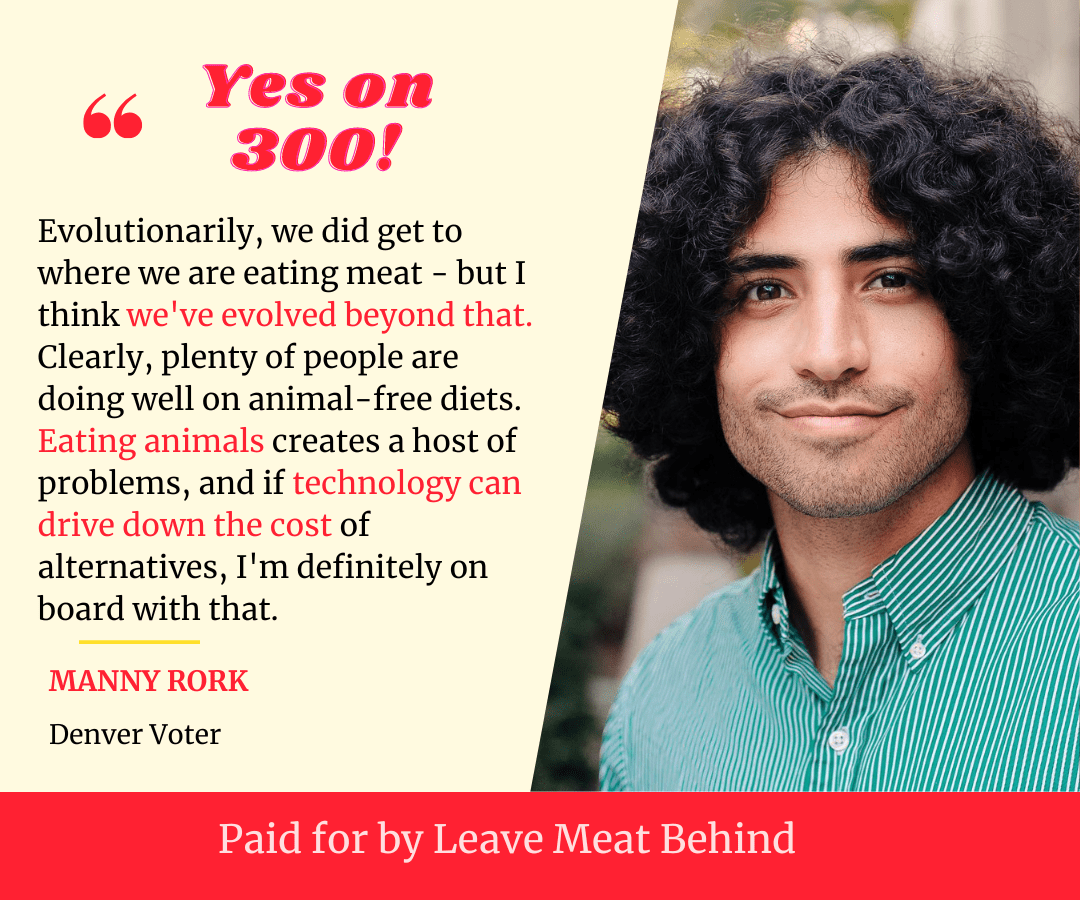

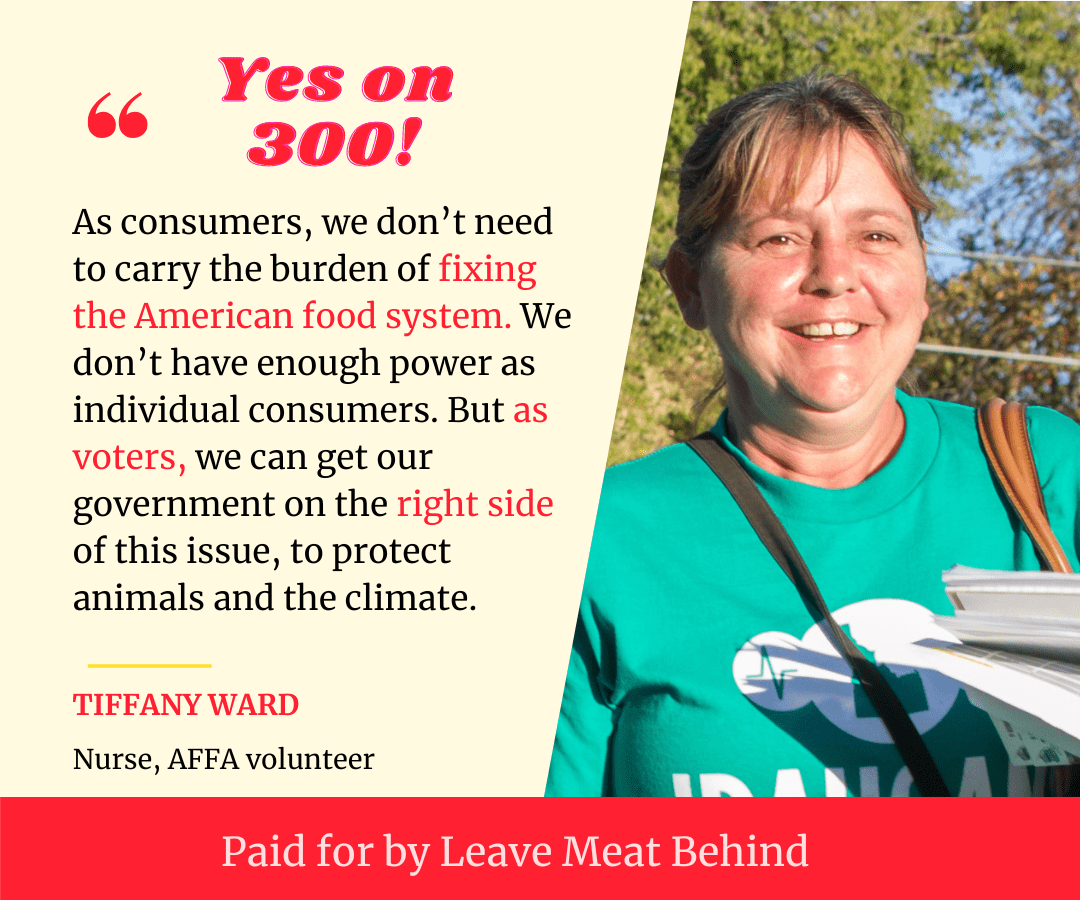

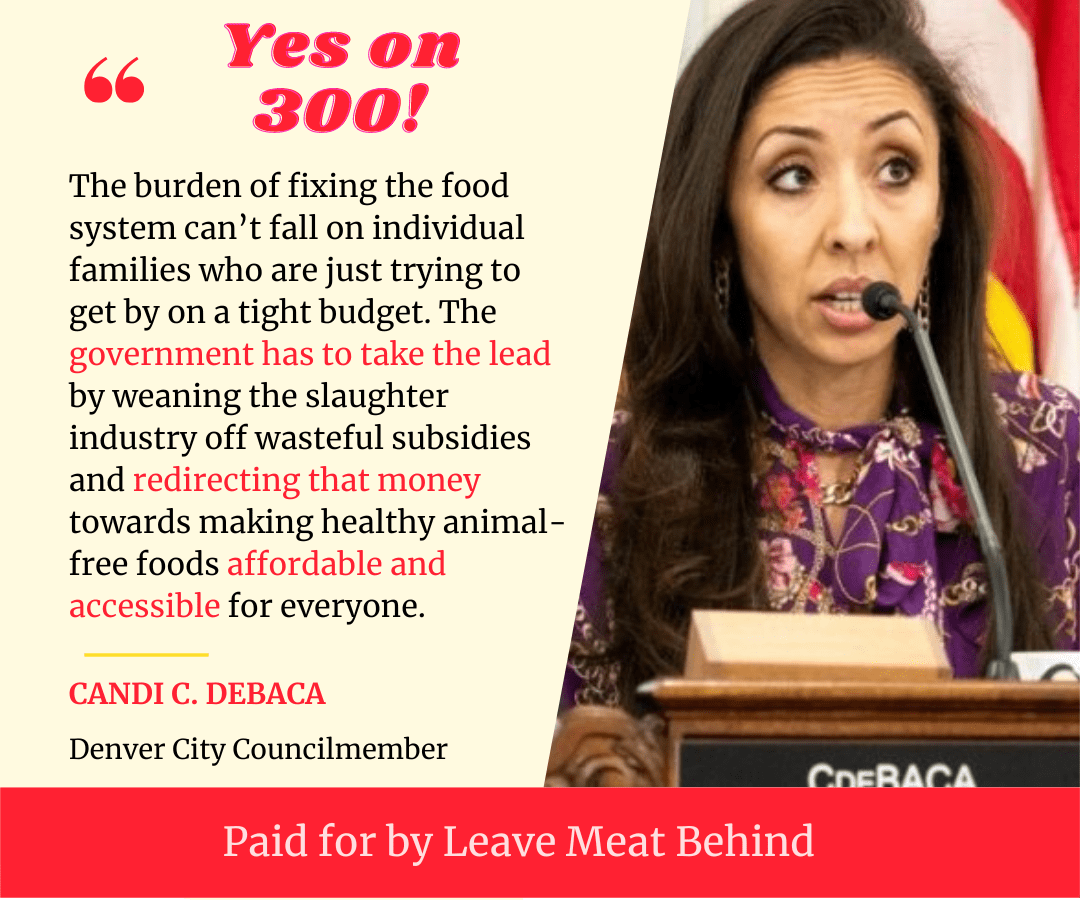

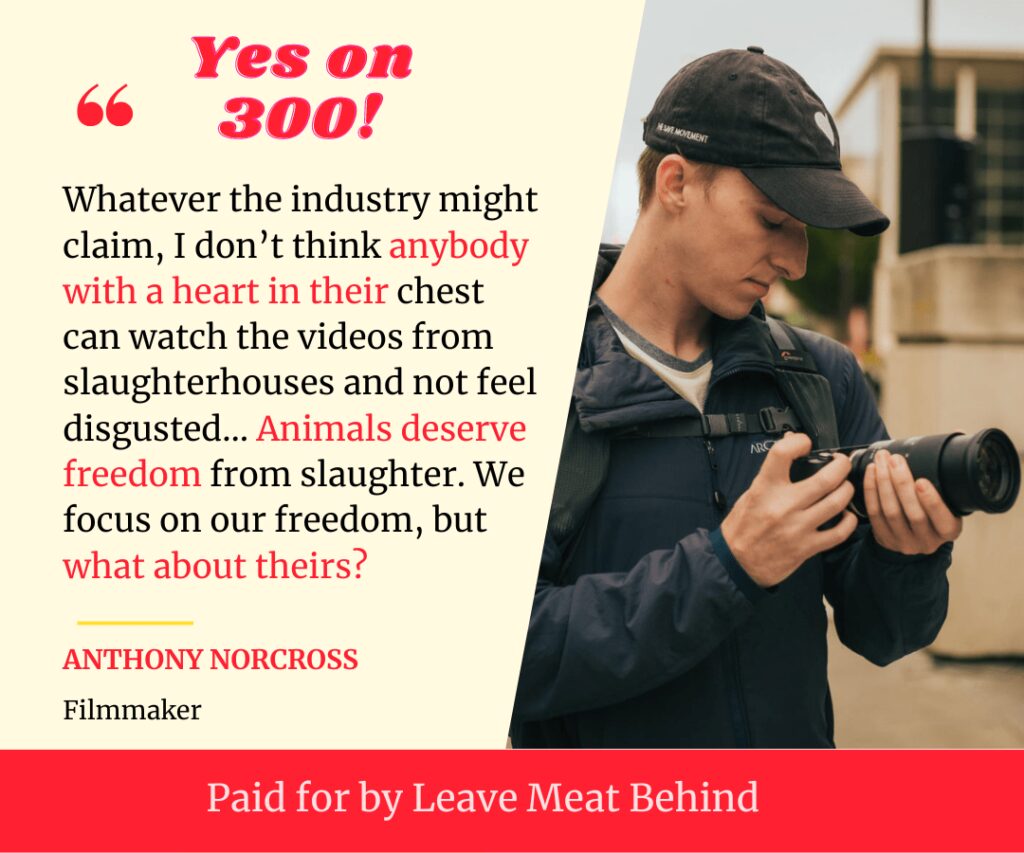

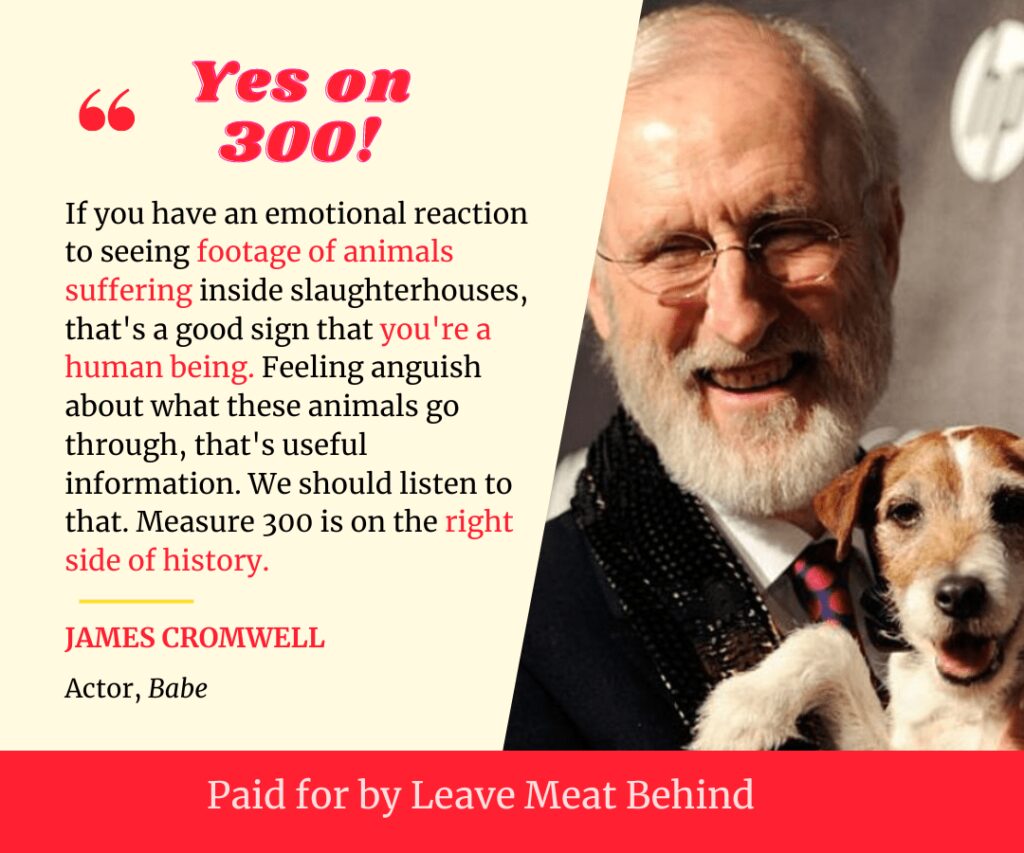

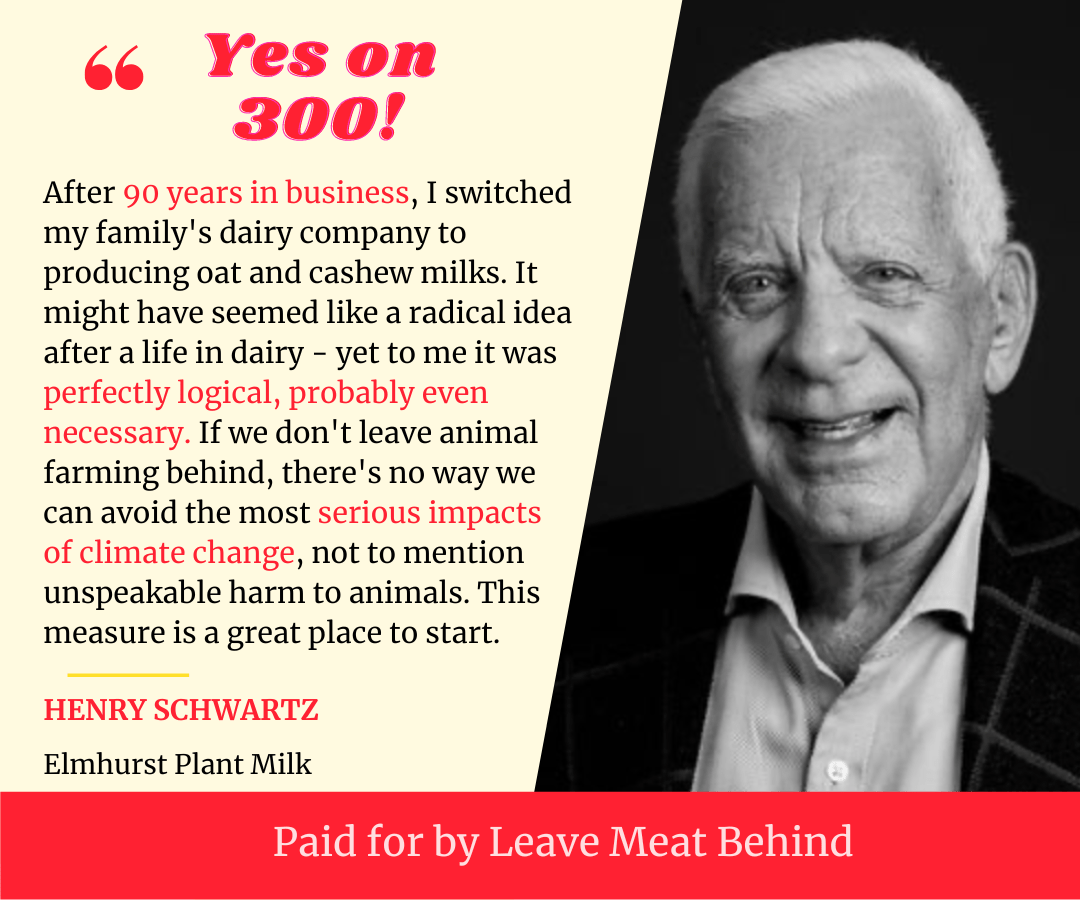

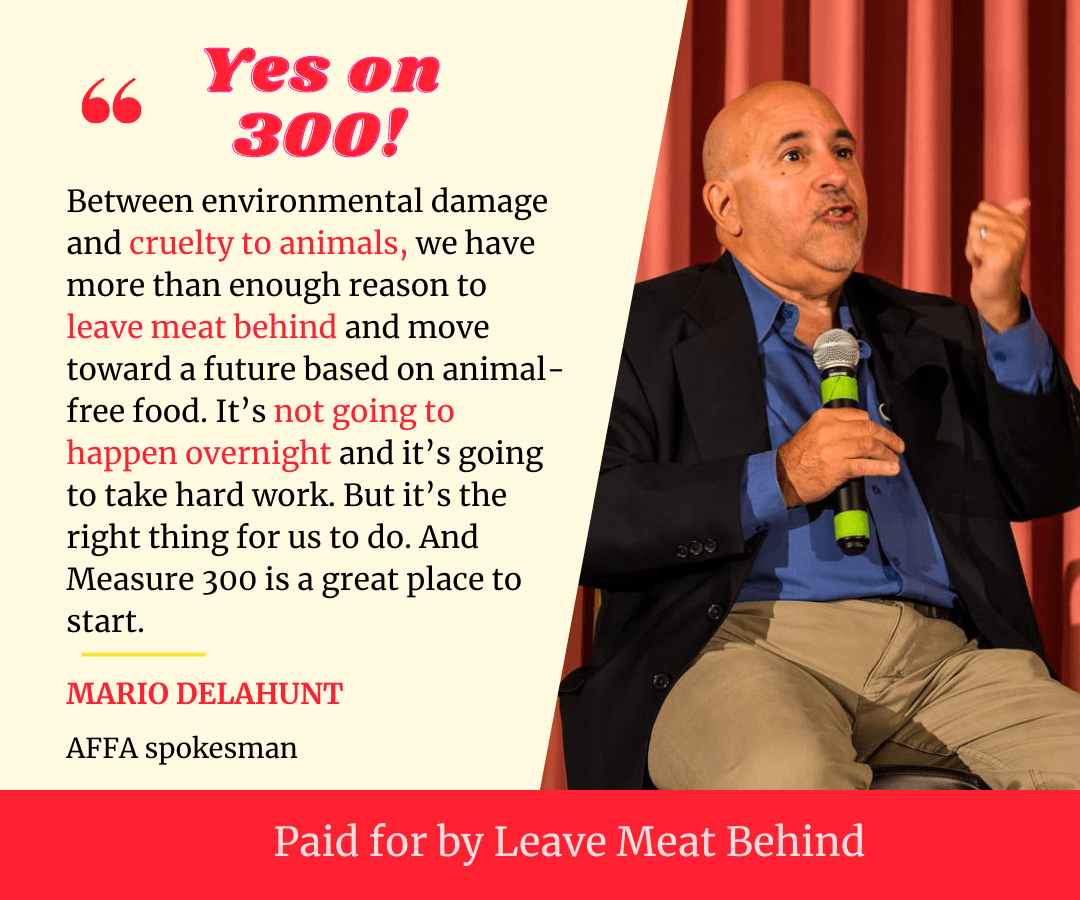

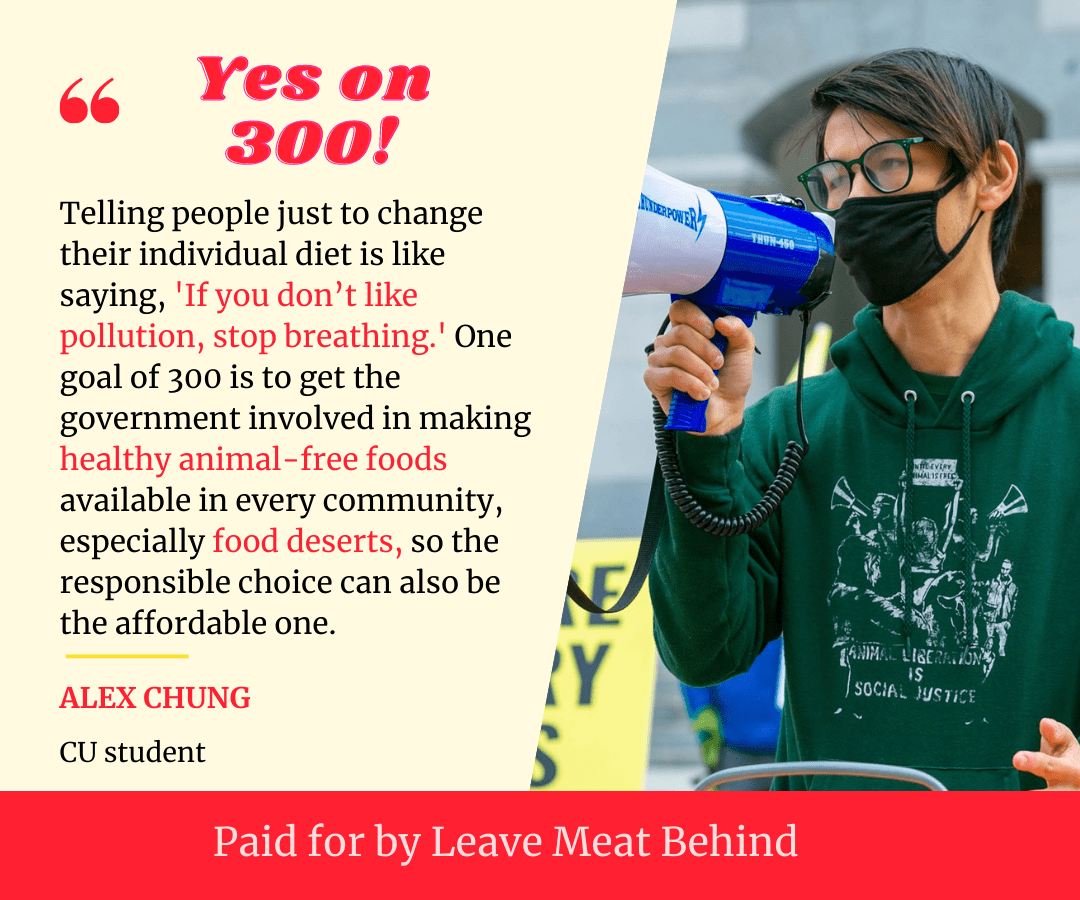

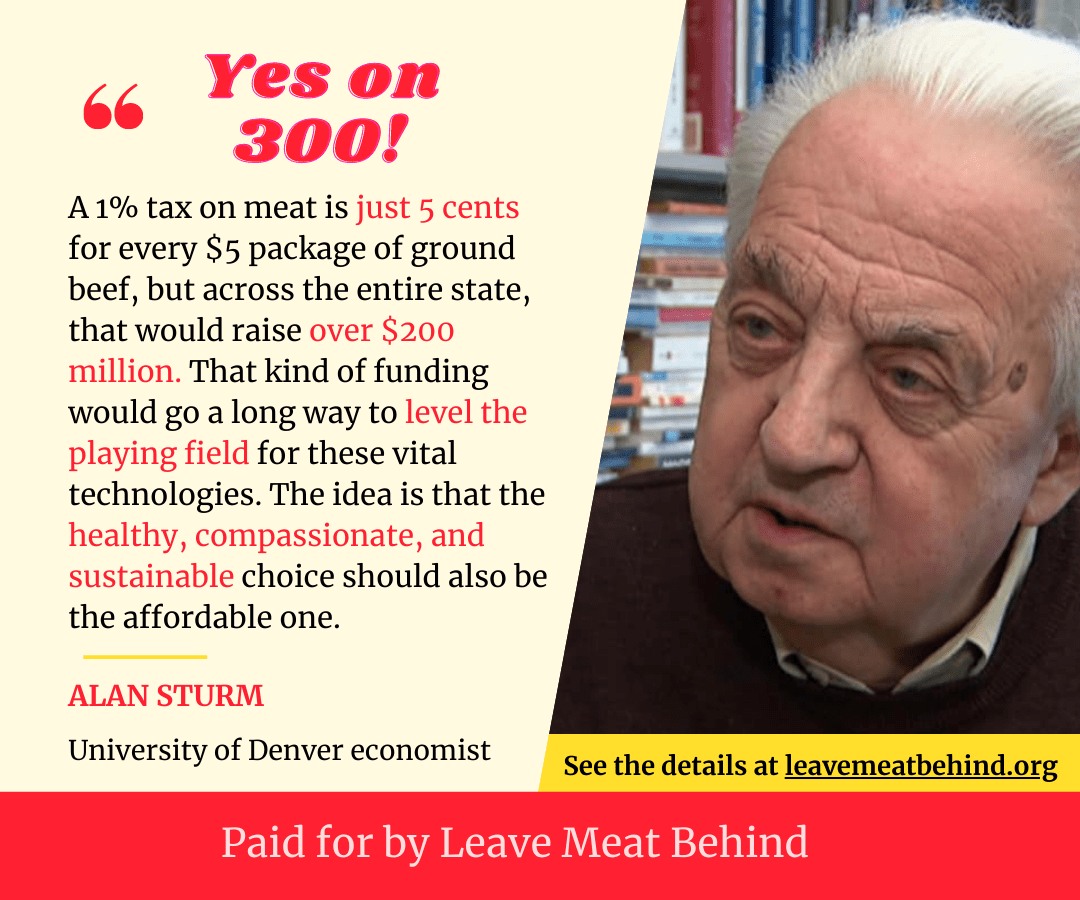

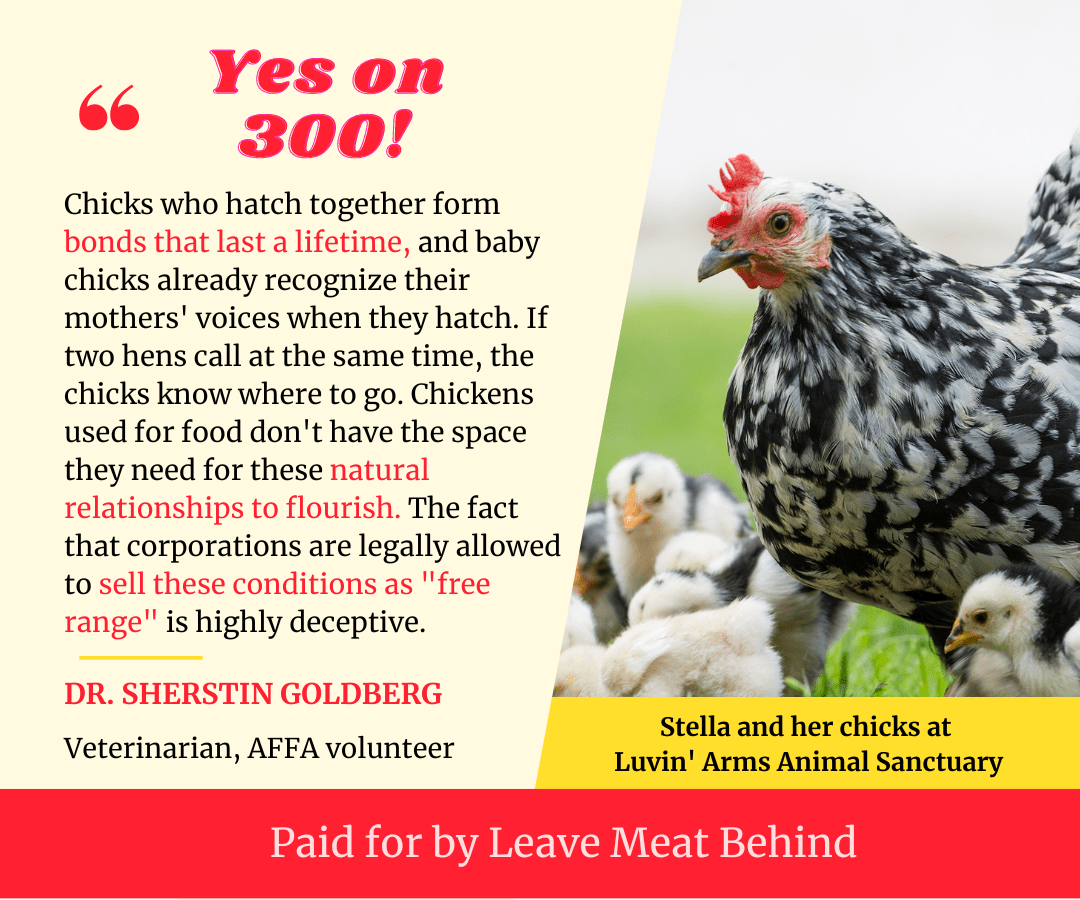

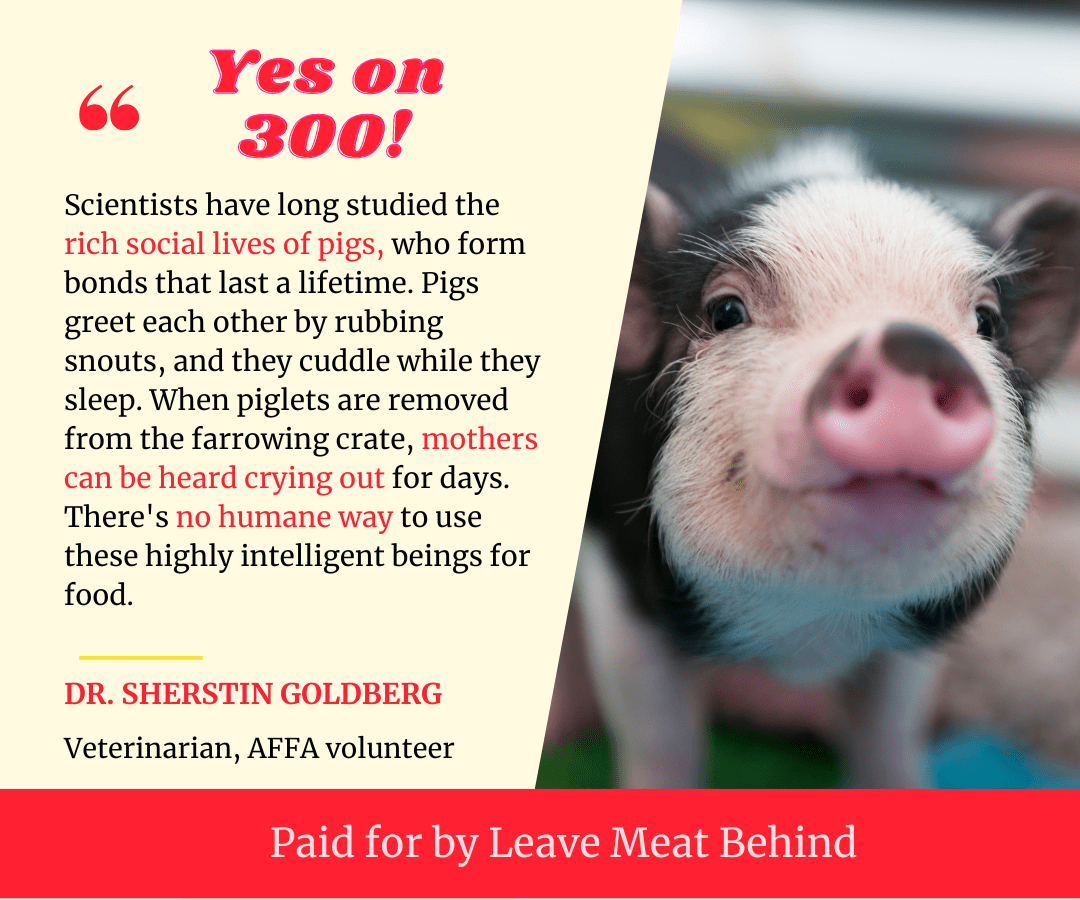

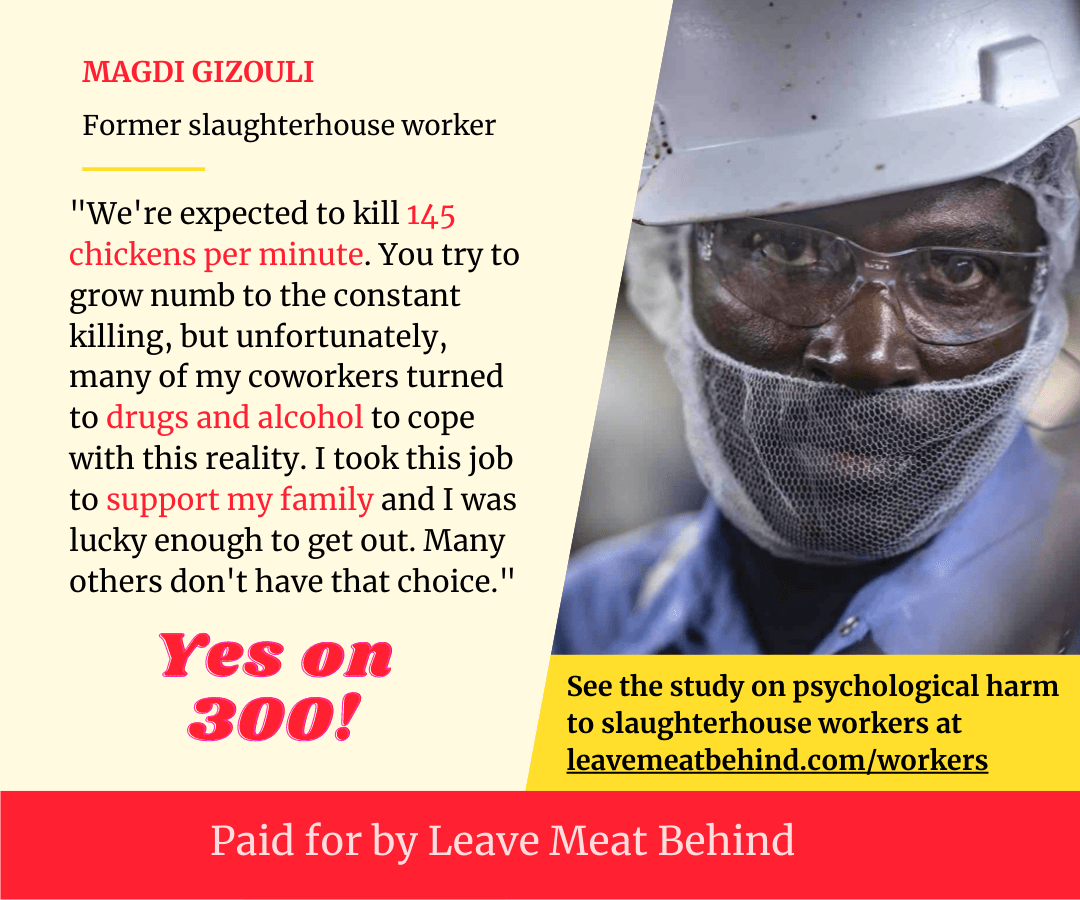

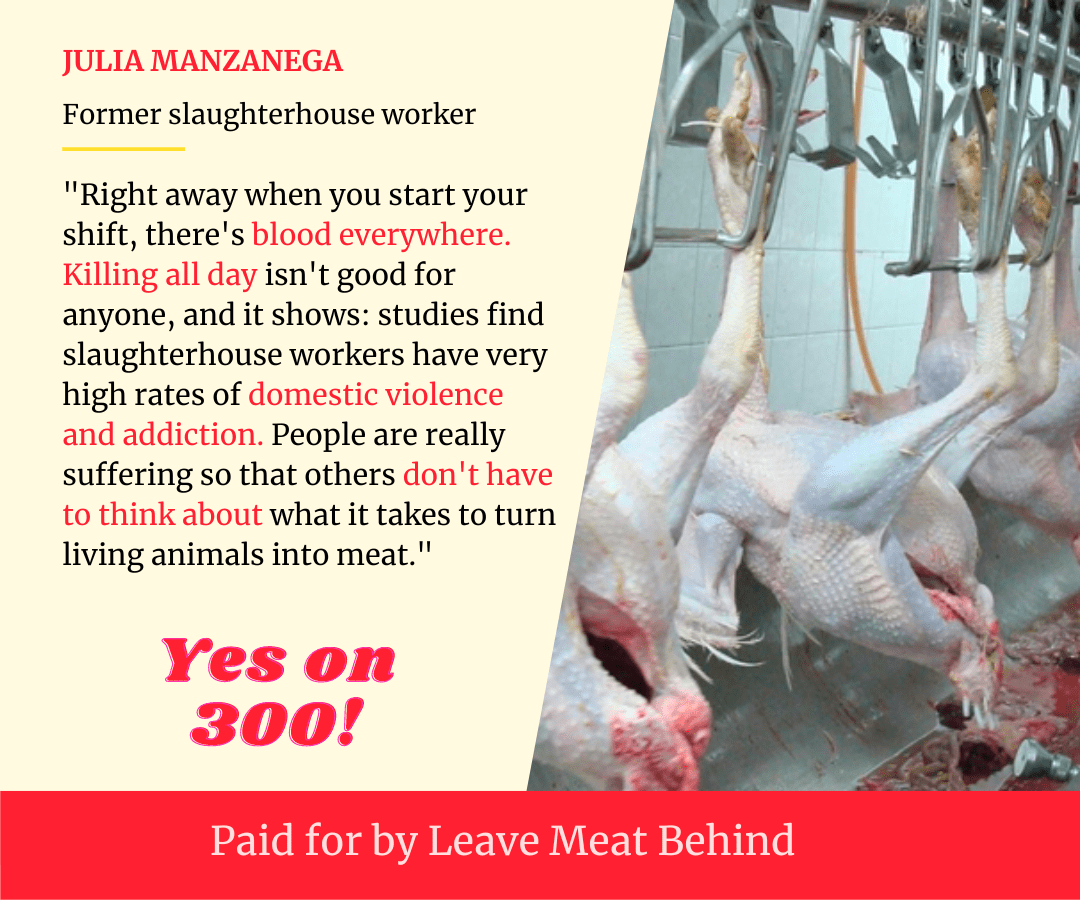

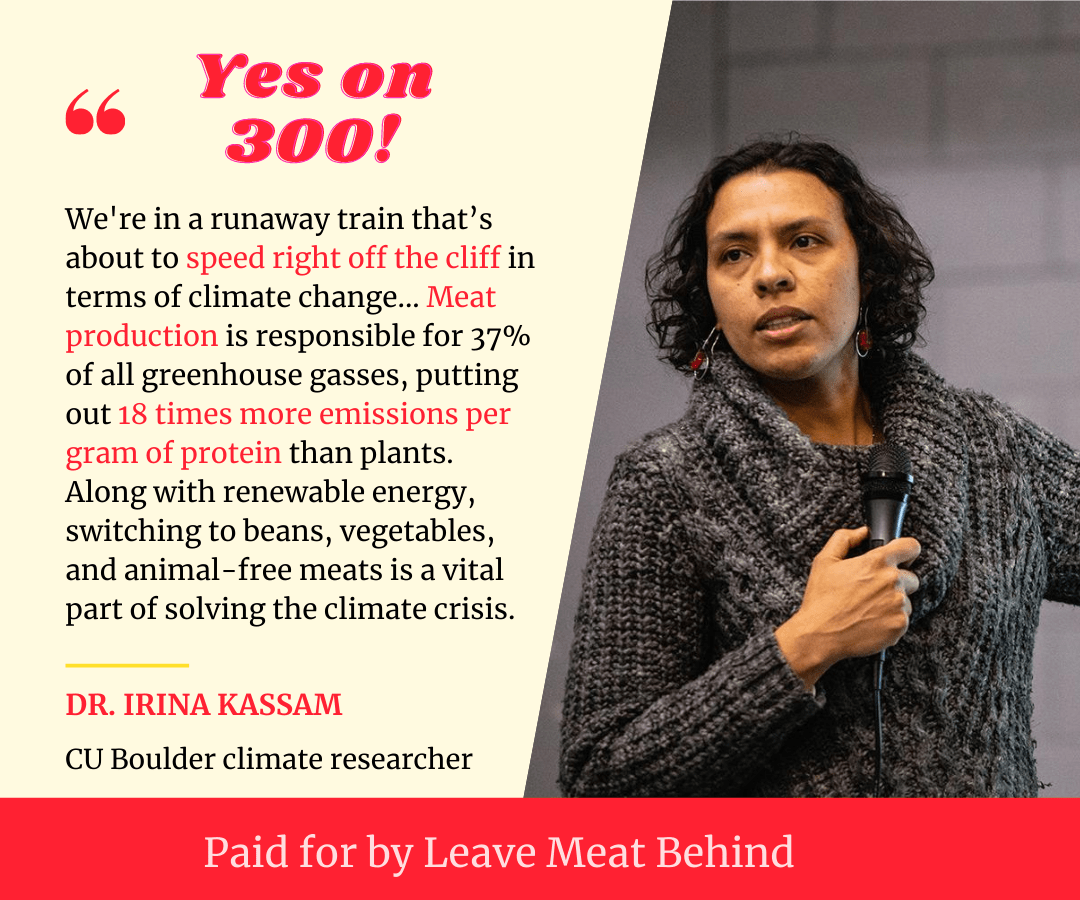

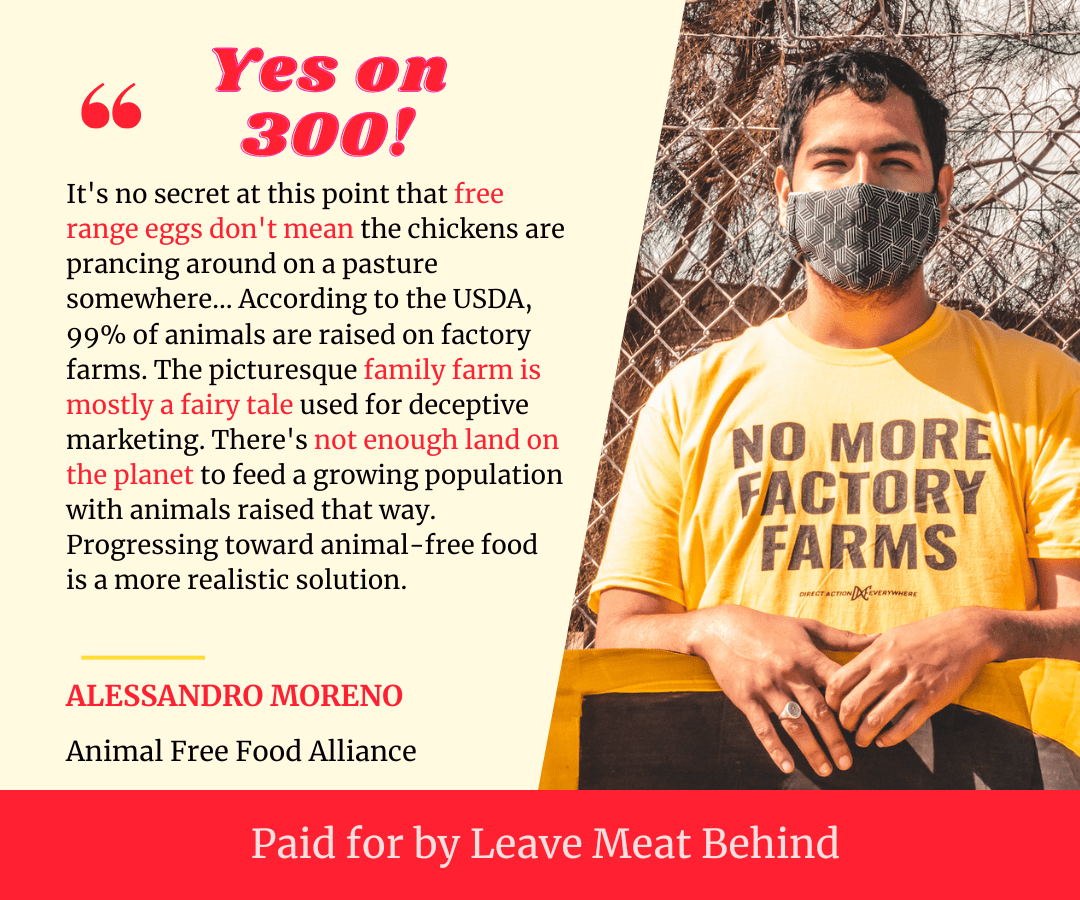

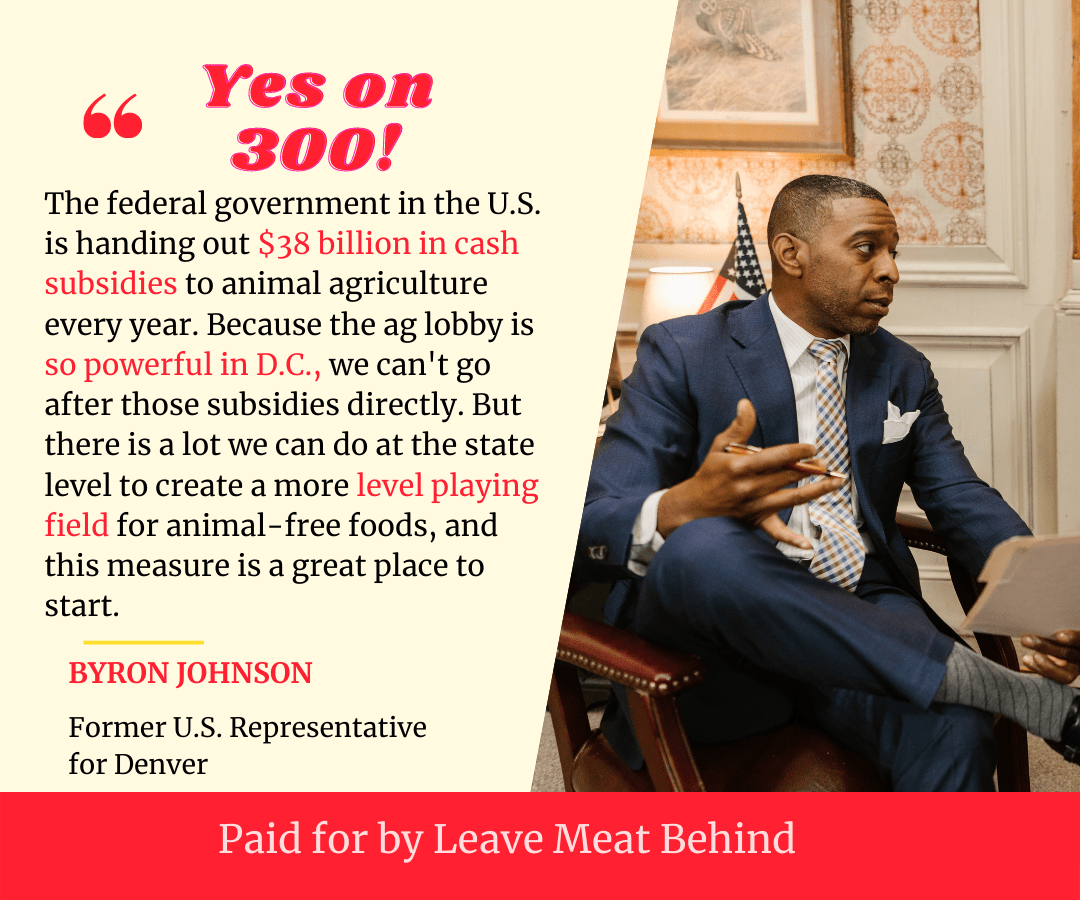

In the latter 20 groups, we replaced the long-form news article with a sequence of short stimuli formatted as social media ads such as the image below. First, participants were told about the fictional ballot initiative. Then they read and reacted to one quote at a time. This change was meant to further simulate the way most people will interact with advocate messaging in the real world (e.g. via social media ads). A mix of real and fictional messengers were paired with fictional quotes that continued to develop based on feedback from focus groups. (To be completely clear, we are not recommending advocates fabricate quotes, but use these recommendations to inform what they themselves say.)

Interviewers limited their questions to simply repeating quotes from the stimuli, along with a few other pre-scripted questions. All scripts and stimuli are available in the materials.

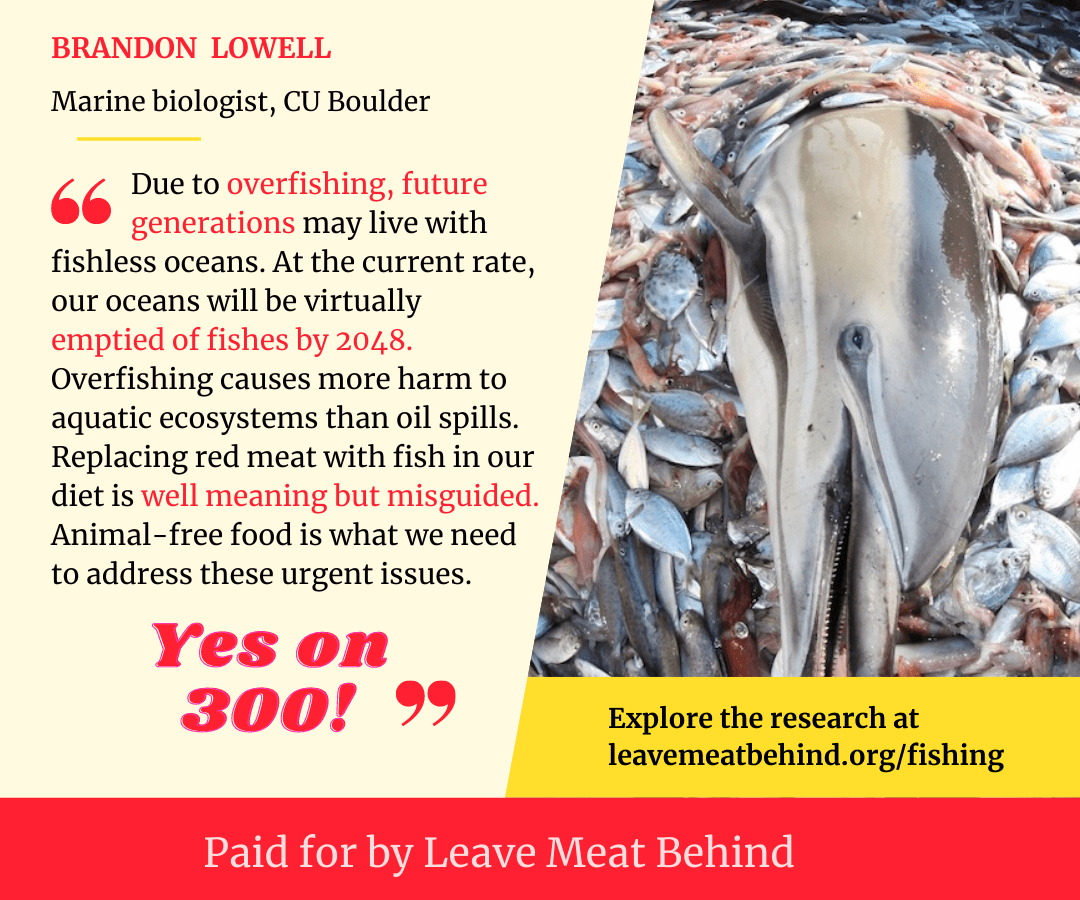

The image below is an example of a social media ad-style stimulus. These images typically featured fictional names alongside stock photos or photos of our associates, though some used recognizable celebrities. In all cases, the messages were designed by our research team. The image was meant to mimic one that might be seen during a real ballot measure campaign, thus a “paid for” statement and a number for the measure were included. The format and colors were identical for all images; only the photograph, quote, and description of the messenger changed.

3. Elements of Messaging

Over the course of this study, we tested the potential of dozens of new narratives to build support for the animal movement. We also looked for lessons in how those narratives could be effectively packaged and presented: for instance, the emotional tone of the message, or the messenger delivering it. We’ll discuss those lessons first because they informed the design of the candidate narratives discussed towards the end of this report.

3.1 Latent Public Support is Widespread but Shallow

We entered this stage of the research feeling optimistic. Our individual interviews had found promising results. We were also still thinking about survey findings such as those by Sentience Institute and Oklahoma State University suggesting that as much as 48% of the American public (and even more so among liberals) would support a ban on slaughterhouses. In our earliest focus groups, we paired the highest-performing language from the individual interviews with a fictional ballot measure that would ban slaughterhouses in Colorado in 6 years.

The response foreshadowed patterns of unexpectedly strong opposition that would persist through the rest of the study.

“Reduce It, Don’t Ban It”

For most of our participants, meat is seen as problematic, but not inherently wrong. They are aware of and at least passively concerned with the harms caused by meat production, but very few people think they warrant abolishing animal agriculture. Instead, they feel that the problems can be addressed by reducing meat consumption or reforming the industry.

The kinds of objections people made to a real and specific policy measure differed somewhat from the more general pro-meat rationalizations we had encountered in individual interviews. Futility, culture, and naturalness were less common. The most common were:

- Concerns about the affordability and accessibility of animal-free foods. Several participants brought up food deserts and worried about what food people living in them would be able to buy.

- Dissatisfaction with the taste of meat alternatives.

- The belief that more research is needed to confirm that new animal-free meats are safe.

- General concern about “extreme” change happening too fast.

- Anger about infringing on people’s personal choices and autonomy.

The topic of using animals for food appears to bring out libertarian instincts among even dyed-in-the-cotton Liberals. Objections to a ban often centered around values of free choice, and participants suggested far less impactful alternatives intended to preserve choice. They often explicitly referenced the market when describing their preferred solutions. Common counter-proposals involved educating the public, subsidizing meat alternatives, and taxing meat.

I think we should definitely have a more gentle stance instead of the use of the word ban, maybe providing people motivation or incentive to try, you know, eat more plant-based products, rather than just completely ban stuff…

Liberal woman, 36

I've wanted to like cut down on eating meat, to at least have one day a week where I don't eat meat. But I think this is really unrealistic. I mean, the way if you really wanted to get people to stop eating meat, probably the pathway to that is to subsidize cheaper alternatives, so that people will just naturally gravitate towards buying cheaper food.

Progressive man, 27

I also think that completely banning meat, farming and selling it is impossible. There's no way that that's ever going to happen. So I think the real solution would be to educate people, instead of restricting it at all. Because people are gonna find a way to get it anyway.

Liberal woman, 22

If I were to go to a bunch of even liberal people today and be like, ‘let's ban meat.’ I don't know if more than 10% of them in that room agree with me… a meat tax, you might be able to get that by. But to ban it?

Progressive man, 27

Conflating Slaughterhouses and Factory Farms

The extremely low support we found for banning slaughterhouses led us to conclude that something is amiss with earlier surveys. One explanation is that many members of the public do not appear to differentiate between factory farms and slaughterhouses. This is an example of advocates overestimating the public’s knowledge of a topic.

Many interviewees were not aware that animals are raised and slaughtered at different facilities. They lump footage they have seen of factory farms and slaughterhouses into one category: a bleak industrial facility where meat is produced. Several participants mentioned slaughter in the context of factory farms or mentioned crowding and cages in the context of slaughterhouses.

There may be other reasons that surveys find unrealistically high support for banning slaughterhouses. While we do not provide a definitive answer, we recommend advocates not rely on that survey data until further research can clarify this discrepancy.

The Hostility of Groups

Participants in group interviews were considerably more resistant to animal advocate messages than those in individual interviews. The presence of other meat-eaters provided reminders of the dominant narrative and created social pressure to conform to it, or offered social cover to state pro-meat positions which others in the group shared but about which the individual may privately feel ambivalent. One participant asserting a dominant pro-meat narrative would often cause the other participants to become more hostile to advocate messages. In individual interviews, we had come to expect participants to be willing to show vulnerability about their conflicted feelings about meat. But when participants felt discomfort in group interviews, they often responded by bonding with other participants about negative experiences with meat alternatives, or with vegans. Such comments proved to be a sure way to get laughs from other participants.

Even group size mattered. Due to no-shows, we had a number of interviews with only two participants. Participants in dyad interviews were usually more receptive than larger groups, and to a lesser extent triads were as well. This is consistent with a large body of literature in economics and psychology suggesting that individuals are less likely to make moral decisions while in groups than alone.

Animal advocates should consider how to bring their message to people when they are alone, or in very small groups. For individual outreach, this lesson is simple enough. But organizations can also think about how to craft messaging strategies that reach people while they are alone.

Underestimating Support

Another explanation for the relative hostility of group interviews is that participants believe other people are more hostile to animal advocate messages than they themselves are. This would be consistent with other research showing people’s tendency to mask views they believe are politically or socially divergent while in groups, even when those views are in fact widely held. In the individual interviews, many participants expressed moderate support while believing their view was a small minority:

I would support it. I don't think I can imagine it because I feel like too many people like meat. But I mean, I could be wrong, you know, one day this could happen. And it would be a huge step forward and a huge benefit.

Conservative woman, 30

I would definitely go that route… But again, this seems impossible to implement. People will fight back, as you're trying to take over their liberties, their choices to make these decisions for themselves.

Liberal man, 26

I would definitely be able to transition. It may be harder for other people, because they may not know what to eat, or how to make the food or what foods are out there… But for me, I'll be able to make that transition pretty well.

Progressive man, 29

While support for an outright ban on meat is currently low, there is widespread discomfort with meat which is not visible to most people. Because meat is so normalized, they believe their discomfort is unique or rare. To address this, advocates should find ways to make latent support for their cause more visible.

3.2 Reassessing Futility and the Evolve Together Frame

In individual interviews, we found that futility was the most persistent messaging obstacle for animal advocates and that the metaphor of evolution was a promising way to overcome futility. We therefore used the evolve together frame centrally in stimuli for the focus groups. While opposition was higher in the early group interviews than it had been in the later individual interviews, futility played a much smaller role, with objections instead focusing on the affordability of animal-free foods as well as infringement on consumer choice.

Evolution may have been partly responsible for this, though another obvious explanation is that the participants were presented with a news article about a ballot measure “designed to accelerate society’s transition away from using animals for food” and the existence of such a ballot measure made drastic change seem like a real possibility. Shortly, we will discuss how the presence of a highly ambitious policy proposal made people support higher-impact proposals than they would otherwise, demonstrating the radical flank effect. Together, these findings point to the tremendous agenda-setting effect that a highly ambitious ballot measure could have on the debate about using animals for food.

On its own, the evolve together message continued to elicit positive responses, and the language of evolution stuck with participants. Respondents appreciated the implication of gradual change. Along with the ballot measure, the evolve together frame helped interviewees understand that the ask was not for them to immediately go vegan, the demand they are used to hearing from animal advocates:

I like the way that they described it as well, because they specifically called it an evolution away from meat, meaning they understand that it's going to be a process, it's going to take some time. It's not going to be an overnight, ‘Oh, well, you know, no one can eat meat anymore.’ It's just a slow process of everybody getting used to the changes and just adapting to a new style of life.

Liberal man, 24

I'm looking at this and I don't think it's very incendiary… I also like the wording, how it's an evolution away from meat.

Liberal woman, 28

I really believe in us evolving away from eating so much meat even though I'm not a vegetarian, and I love beef especially and it's very painful to think about. But I really think we've got to do it…

Progressive woman, 71

3.3 Tone: Facts and Feelings

What tone should animal advocates use when addressing the general public? When are emotional appeals effective, and when do people respond better to a more cool, rational tone? What is the role of hard facts in messaging? These questions are crucial, as the wrong tone gives people an excuse to dismiss or ignore advocate messages.

Our findings on tone were complicated and somewhat contradictory. In short, most participants insisted that they prefer an emotionally neutral message focused on facts. Yet when presented with facts, the most common response was to question their credibility. Meanwhile, while overtly emotional appeals were ridiculed and dismissed as manipulative, more subtle appeals to emotion (e.g. with images) had an obviously positive effect.

Here, we attempt to unravel these contradictions and make suggestions for how advocates can thread the needle between facts and emotions.

Ambivalence Towards Factual Assertions

During focus groups, we often noticed an antagonistic feeling between the participants and the messages they were being shown. One of the most common ways participants sought to poke holes in the test messages was by saying they lacked information:

I think the best way to go about this would not be [to make analogies]... if they can compare [animal and plant-based meat], just side by side, and give some facts about each side and show why you know, plant-based meat can be just as natural if not more than regular meat.

Conservative man, 23

Although I like the idea, I think they could add more detail like how they think one is better than the other.

Moderate man, 25

[It needs] more facts that are going to tell me why I really should support it.

Progressive woman, 22

I think I would lend my support towards it. But I would also just just want to know more information… there was a lack of sources, a lack of proper citations and a lack of a lot of the numbers and background information. So while I would support a measure like this, I just want to know more.

Liberal man, 24

...if you're not going to cite something, don't say it.

Liberal woman, 44

Yet when facts were presented, participants frequently responded with several ways of dismissing them. They asserted that without giving lengthy context, the facts could be misleading. They would point out the lack of a citation, even in a two-sentence quote on a social media ad. If a citation was provided, they might question the intentions of the researchers or their sponsors, or else describe feeling lost in a maze of contradictory science, especially about health topics but also more generally.

[Responding to a quote from a doctor] “I feel like this statement is not necessarily completely correct, I don't think it really paints the whole picture… I just feel like [he’s] a TV doctor, kind of just like, ‘I'm just paid for this to say whatever.’ I hate these types, because I feel like it's irresponsible for someone in medicine.”

(Liberal woman, 37)

I'm wondering where they did that study… I think the way this is written is meant to be like a little thought piece that was just thrown out there. So somebody looks at the numbers, and then that's what sticks with them. So then if it comes up in conversation with someone later, they cite the numbers, even if they don't really know where those numbers came from. Um, and it's effective in terms of advertisement and getting your message out, but at the same time, especially because we don't know their sources or any of the background information overall. That could be potentially pretty misleading for a lot of people.

Progressive man, 29

The thing about studies is like, one minute, something will be bad for you and cause dementia, and the next week or the next day, it's the complete opposite. So I don't really pay attention to studies anymore. One day drinking three cups of coffee is bad. And the next minute, it's like, ‘oh my gosh, you need to drink at least three cups of coffee to live until you're 70.’ So I don't really pay attention to studies like I used to.

Liberal woman, 45

I don't like when people state things and don't mention their sources.

Liberal woman, 28

Interviewees’ ambivalence towards factual claims suggests a deep distrust of political messages and a sense of helplessness in not knowing what to believe in a political landscape fraught with dishonesty and deception.

Citations Provide Legitimacy

Though imperfect, the most effective strategy we found to respond to this skepticism was including citations. On any slide that contained a factual claim, participants appreciated a link they could hypothetically follow to learn more and see the data behind the claim. Participants were not able to use these links during the interview, and we are skeptical that many of them actually would closely scrutinize this data to confirm the claim. But the mere presence of a link was reassuring and significantly reduced participants’ tendency to dismiss factual assertions.

I appreciate that they put percentages and facts, if you can verify them in [the link]. Because numbers speak to me… I don't want it to just say, ‘it makes greenhouse gases,’ that doesn't mean as much to me as saying ‘it makes 37% of all greenhouse gases.’ I appreciate that.” (

Progressive woman, 29

I like that there's some statistics in here. And I particularly like the link where I could do more. I'm a kind of a researchaholic and I would definitely, if this was something I was interested in learning more about, I would definitely take advantage of that. So I appreciate how this slide seems more scholarly, which appeals to me.

Liberal woman, 60

We recommend that advocates provide something resembling a citation as often as possible in messaging. In written messages, we recommend advertising a link where people can learn more or see the data behind a claim. We doubt that many people will click through, but this can help build trust with the public. Of course, the link should provide the relevant information for those who do investigate, and advocates should be aware that even slight exaggerations of factual claims will make it easier for people to dismiss our message outright.

Emotional Appeals Are Seen as Manipulative

Conventional wisdom among political campaigners holds that voters are more influenced by emotional appeals than detailed arguments about policy. But this is certainly not how our focus group participants thought of themselves. On the contrary, one of the most common reactions was to reject messages seen as appealing to emotions. Such messages were seen as manipulative and offended participants’ view of themselves as rational decision-makers. Men in particular resented emotional messages:

This cheapens the credibility of this organization, that they're playing so deeply on the emotional card here.

Liberal man, 62

It feels manipulative, in the same way that like hunger companies will use the poor starving kids and like a third world country looking sad at the camera, it gives me that vibe. So it's like you're trying to like pull the heartstrings and kind of manipulate me emotionally.

Progressive man, 25

This does appear to be an appeal to emotion. That's why the pig's name is given in the paragraph. The only reason for that is to make it more personal so that the reader relates to it more.

Liberal man, 31

I do like statistics, I would like to see less hyperbole and less emotion. I'm not persuaded by that.

Liberal woman, 60

Any language seen as too strongly worded or too absolute was likely to receive this backlash. One participant even objected to “at all” in a message stating “There’s not enough corporate responsibility at all.”

However, while many emotional messages evoked a negative response, leaving emotions out entirely was also ineffective. Without drawing an emotional connection to the suffering of animals in farms or the consequences of environmental destruction, participants viewed the entire conversation as irrelevant and dismissed even the mildest policy measures (such as subsidies for meat alternatives).

Three Strategies for Emotional Appeals

We tested messages with a broad range of emotional registers, from emotionally sterile to very dramatic. We identified two promising strategies for advocates to incorporate emotions into messaging.

#1: Don’t Be Cringe

The first strategy is simply to appeal to emotion using a more restrained tone. We could not find a better way to describe this strategy than in a simple rule of thumb: don’t be cringe. Advocates may be tempted to use emotionally intense language to try to grab the public’s attention, but they should be aware that this language may repel many listeners, to whom it seems hysterical or manipulative.

One easy way to adjust the tone of a message is to limit the use of adjectives and adverbs, especially absolutes such as always, never, or at all. Another is to replace statements with questions, even obviously rhetorical ones. For instance, after receiving feedback, we changed a sentence in one test message from “We have no right to keep doing this to them” to “We focus on our freedom, but what about theirs?” This small change significantly improved responses to the message, which was otherwise one of our most emotionally pointed.

What both suggestions in the above paragraph may share in common is leaving more room for the listener to define their own thoughts and feelings about a topic. We suspect that messages full of emotionally charged adjectives (e.g. “outrageous”) may draw a backlash because they feel emotionally prescriptive. Instead, we recommend advocates try to leave some room in their messages for the listener to make connections and come to conclusions on their own. Indeed, the same principle may explain why images were also an effective strategy for emotional appeals.

#2: Let Images Do the Talking

A simple way to appeal to emotion without appearing hysterical is to rely on images to create an emotional connection with the message. Yet even some images can be seen as manipulative and invoke an anti-emotional response. In our focus groups, images of happy, healthy animals struck a good balance, creating an emotional connection without eliciting a backlash. Participants rarely suggested these images were proof that humane farming was possible; instead, they described feeling more connected to the animal and more discomfort with the reality of slaughter.

More graphic images of farms and slaughterhouses were powerful as well, though they tested and sometimes exceeded people’s tolerance for overt emotionality. Advocates should be aware that showing images of slaughter may be seen as manipulative. Advocates whose messaging strategy relies on being seen as trustworthy may want to use such images sparingly.

Images (such as the one below) of animals’ bodies after slaughter, but before being dismembered into familiar “meat” products, also struck a very effective balance. These images elicited disgust and bridged the mental disconnect between animals and meat. We recommend advocates make far greater use of these images to create a visceral reaction, generating disgust towards meat and making the larger subject of their advocacy emotionally relevant to the audience.

Most people will have a similar emotional response to the image above. But our interviews suggest that in reacting to a photograph, the viewer feels that their emotional response is their own, rather than being prescribed to them:

I kind of liked the ad, because it's so brutal. I feel like some people need to see this type of image to wake up.

Progressive man, 26

The first thing screaming in my mind is just ‘Yikes, oh my gosh.’ And it's kind of just leaving me with nothing, because I could never imagine myself doing that…

Liberal woman, 30

Clear, well-lit images of a friendly messenger can also be very effective, especially when the identity of the messenger plays a central role. This case is discussed later on.

#3: Explicitly Target the “Anti-Emotion” Frame

Participants described emotional appeals as manipulative, saying they preferred arguments based on facts and cold rationality. This argument operates in a frame, one we found to be vulnerable. We experimented with messages that preempted anti-emotional backlash by making the case that emotional reactions to violence against animals are healthy and appropriate. After some iterations, we found these messages to be effective:

Earlier versions of these messages used stronger language. For instance, the reference to “history” in the image on the right was originally more explicit: “History has shown us what happens when we suppress our compassion for others.” Respondents registered this as a veiled Holocaust reference and criticized it. The emotional register in these versions was calibrated through feedback from focus group participants. Some participants found these assertions offensive, but most found them compelling:

I think he's right that we should listen to our feelings. I mean, why not? For me, there's a big piece of denial.

Progressive woman, 71

I know that it's coming from a rational place, I think it seems compassionate. And I wouldn't be offended by it. And I don't think it's harsh. I think it's actually on point, what he's saying.

Liberal woman, 38

Because these messages were transparently arguing in favor of emotionality, they avoided the objection of being manipulative. This strategy mirrors the “pulling back the curtain” strategy discussed in the previous report in this series, where revealing the frame behind an opposition argument is enough to weaken it.

3.4 Persuasive Messengers

We can think of messaging strategy as having three crucial components: the message itself, the messenger delivering it, and the method conveying it to the listener (e.g. a billboard, a social media ad, or a speech at a protest). Each is crucially important. The third is beyond the scope of this report, and the second is discussed only in this section. Yet these might be some of our most useful recommendations.

Overall, we found that while authority is often emphasized when choosing messengers, our interviews suggest that relatability and trustworthiness are more important. While there was a space for expert messengers, our participants were more likely to be persuaded by ordinary people, people they could see themselves reflected in. The greatest effect was messengers from demographics people don’t normally associate with veganism or animal rights, and most of all, people who still eat meat.

The Unexpected Power of the Meat-Eating Messenger

As we discussed at length in the previous report in this series, the challenge faced by animal advocates is how to overcome inertia among a general public that is already somewhat familiar with the harms of animal agriculture. Specifically, many people have deeply contradictory feelings about meat, feeling deep attachment to it at the same time as being repelled by how it is produced. We also discussed common defensive reactions to advocate messages, and how advocates might use empathy and even validation to create more openness to their message.

Empathy and validation may be the best options available to an individual advocate engaging in outreach, but at the level of public messaging, organizations have a more powerful tool available: the meat-eating messenger.

The meat-eating messenger is essentially the embodiment of the public’s ambivalence towards meat. They know that meat is harmful and that it would be better overall if we switched away from it. But they still eat it.

The meat-eating messenger melts the public’s defensiveness. On one hand, the person delivering the message still eats meat, so they couldn’t possibly be judging the listener. On the other hand, they demonstrate that it’s possible for meat-eaters to actively support the goals of animal advocates.

The first character playing this role in our focus groups was a fictional woman named Shanelle. In a news article, Shanelle was part of a group of friends deciding whether or not to sign a petition for a pro-animal ballot measure. One friend stated strong support, and another stated strong opposition. Shanelle fell in the middle:

I suppose vegetarians say you don't really need to eat meat. I guess you don't if you can find other sources of protein. But for me, I like a good hamburger, a good steak. But then I feel so bad after seeing all those videos online.

She ultimately decides to sign the petition.

Shanelle’s comment was an amalgamation of real quotes from earlier participants in the study. Her authenticity struck a chord:

There's [dissonance] between what you're doing in the moment… eating some meat, and then kind of having to push away the feeling of guilt or shame. As Shanelle said in her comment, I like to eat these things. But then I feel so bad… but I’m not actually doing anything else about it.

Liberal woman, 28

I think I think this is actually a really good quote, because I feel like this relates to a lot of people because like, even though they kind of feel bad about it, they aren't still willing to give it up.

Liberal woman, 19

I understand that woman. I think she's being honest and open. But it's almost like she has given up a little bit or something. Like, maybe she didn't have any power. Rather than understanding that she does have that power. And that's kind of what we're talking about.

Liberal man, 62

But other participants mistook Shanelle’s message as pro-meat. We wanted to sharpen it, but weren’t sure how far a meat-eating messenger could go before being accused of hypocrisy.

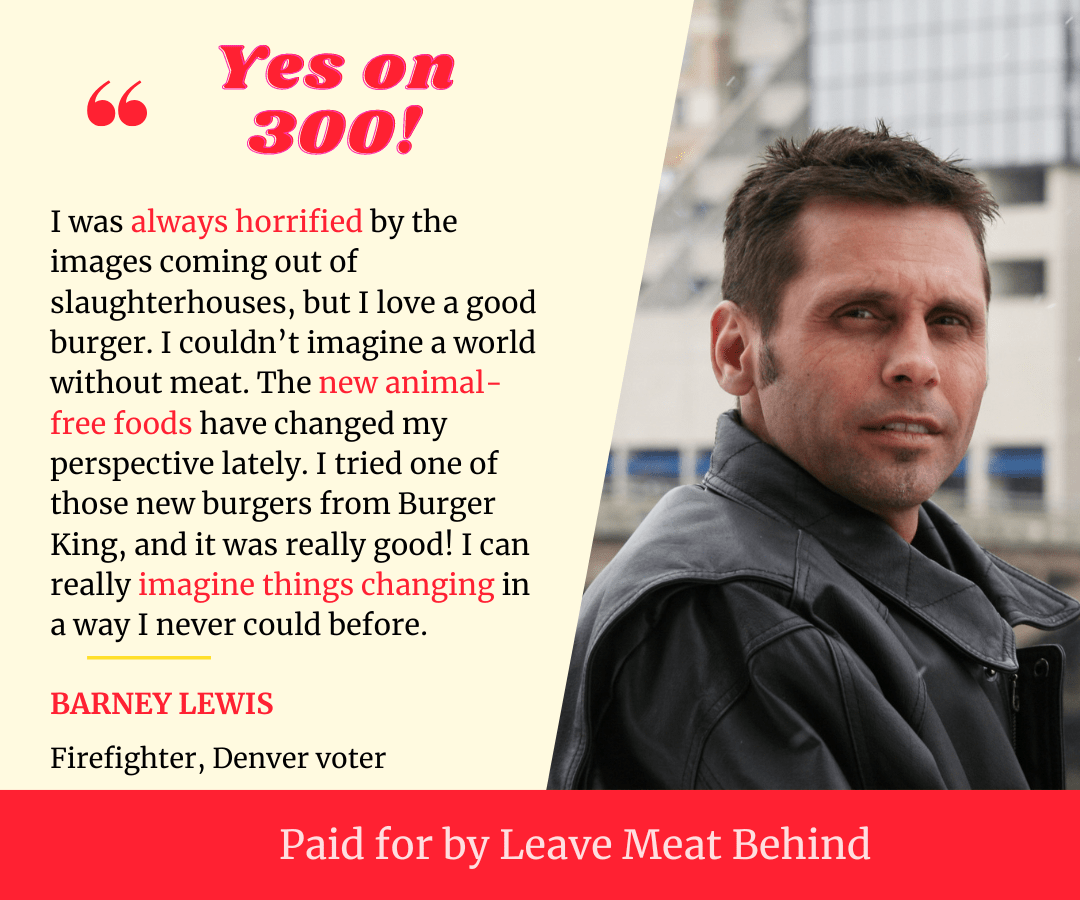

The answer was, very far. We tested extensively with messengers who explicitly mentioned that they still eat meat and found that the many pointed messages were most effective coming from a meat eater.

The only time meat-eating messengers were accused of hypocrisy was when they were also rich or famous. (Celebrity hypocrisy is discussed more below.) The essence of the meat-eating messenger is that they are relatable. Rather than being seen as judgemental, they are seen as honest and vulnerable about an internal struggle that many Americans share, though they try to avoid it. This relatability is enhanced by other features of their identity.

We especially recommend using meat-eating messengers who represent the demographics believed by the public to be the least likely to stop eating meat or support the animal rights movement: working-class people, men, people of color, and older people. More importantly, a diverse range of meat-eating messengers will optimize for relatability.

This is not to say that every message will be more effective coming from an “average Joe” working-class meat eater. Messages focused on facts are more persuasive when delivered by experts. The meat-eating messenger is connected to a specific type of message meant to address emotional attachment to meat. Here are some examples of effective messages we tested that clearly conveyed the messenger’s meat-eating identity while still making a pointed comment in support of the animal movement that could credibly (as our participants were concerned) come from a meat-eater.

And here’s how participants responded:

I like this quote as well, just because I feel like it's very realistic. Like, it seems like it's just like a citizen, like a Denver voter… I feel like a quote from someone who still eats meat would more be more likely to resonate with people who still eat meat. And personally, I kind of agree that they might not taste like exactly the same. But the difference in similarity is worth the payoff for like an animal's life being saved.

Liberal woman, 19

I love this one, I find it to be so relatable. That first line, being horrified about the images and loving a good steak. I feel like that's the tension of so many people that I know, myself included. Just to be able to say that out loud, let's have both of those things be true at the same time. I think that's a really powerful way to start. And coming from a working class American, a firefighter makes it somehow really compelling to me.

Progressive woman, 37

This one's very relatable… it's good to hear from just him being an average voter, you know, his take on it and how he seems to be enjoying the taste, even if it is a little bit different. And knowing that it is a better direction for us to be going.

Liberal man, 32

I just find this really relatable. Because like, I mean, I like impossible burgers. I like regular burgers, but like I'm okay with dealing with a step down in taste but also I'm open to like trying other things that aren't fake meat… So I think it's a better direction to just steer clear of meat.

Liberal woman, 28

Animal Messengers

If the animal could walk up to me and say, ‘Hey, don’t eat me,’ then I wouldn’t eat you.

Progressive man, 34

Even our participants were able to identify the barrier posed by the fact that animals cannot speak for themselves. Or can they?

We wondered how participants would react to a message presented as being spoken by animals themselves. (Many advocates have used images like this before.) Would they find it laughable? We found that with a compelling photograph, such messages were very effective at melting opposition:

This slide makes me feel kind of bad. You know, I look at it and go, Wow, it's really, we're, I don't know… Since I'm not a vegetarian, you know, I guess I don't think about things like this too much.

Liberal woman, 63

It's kind of telling you wake up. You're eating animals. Animals are dying, because of your greed to eat good food, you know? Yeah, that's all I want to say. I like the [picture], it makes you sympathize.

Progressive man, 26

Simple and powerful.

Liberal woman, 43

I imagine if I was scrolling on social media… the first thing that's going to catch my attention is the picture. And so if it's a person, I'm just going to assume it's some other political ad… but animals draw you in. And that's not necessarily quite a political stance at this point. And so you see that you're like, Oh, what's this? And so then I want the text to support whatever is being shown.

Liberal woman, 30

We wanted to use a message simple enough that animals arguably are in fact saying it. After some rounds of testing, we settled on “we don’t want to die”. We also tested “we want to live”, but some participants correctly identified that the goal of animal advocates is for farmed animals not to exist in the first place.

We strongly recommend not only using animal images, but presenting animals as messengers.

Other Recommendations Concerning Messengers

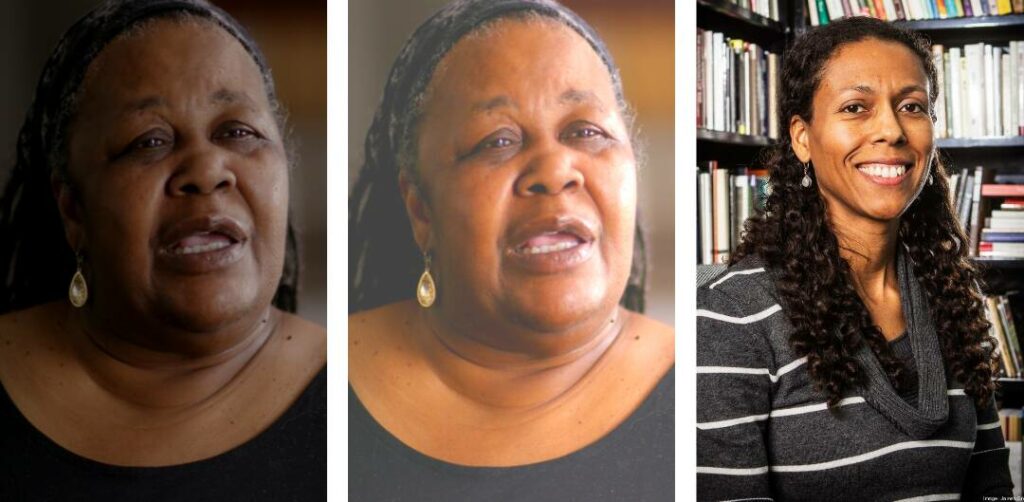

Feature Demographic Diversity, Especially Working-Class, Men, POC, and Elders

Demographic diversity definitely matters for animal advocacy. There was a widespread view among our participants that veganism is for “rich white people rather than other demographics” (Liberal woman, 29) and the younger generation.

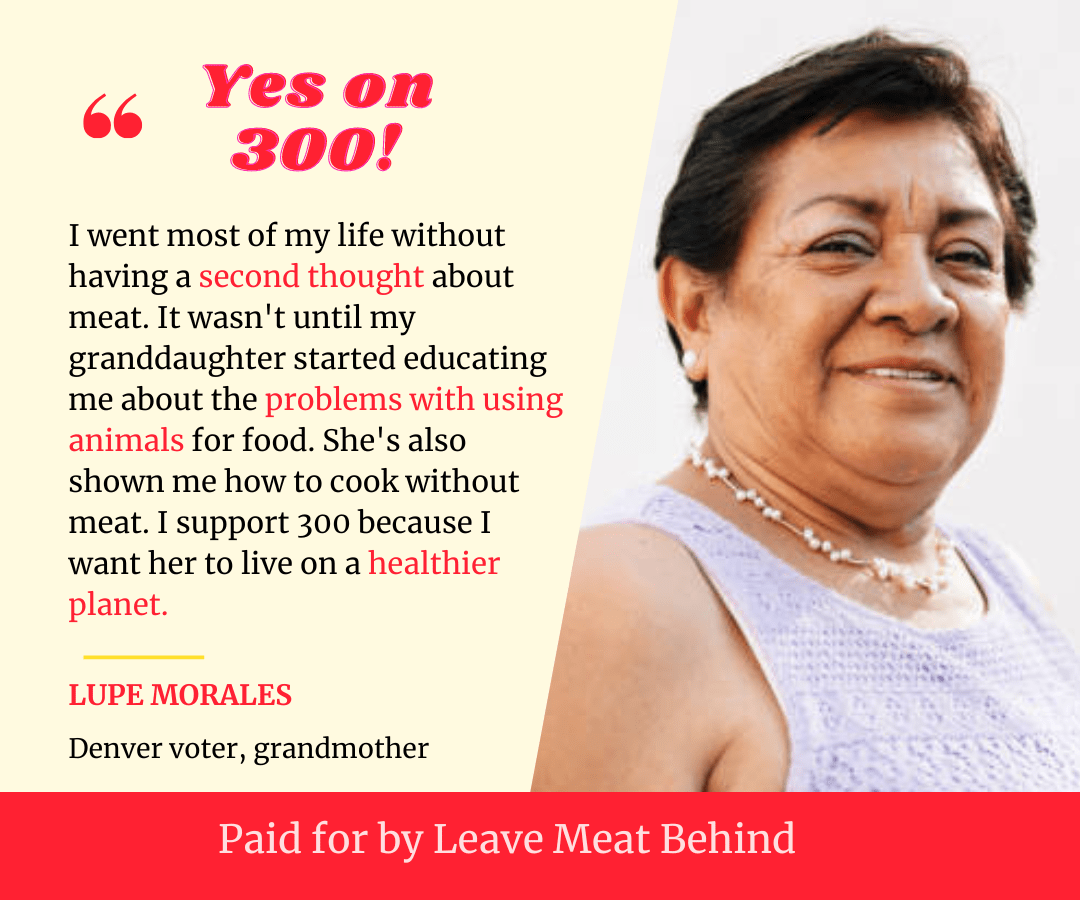

Advocates should take every opportunity to use messengers to subvert these common misconceptions about the animal rights movement. Working-class men, men of color, Black and Latina women, and older people all disrupt these beliefs when acting as spokespeople for the animal rights movement.

Perhaps the most striking example of this in our focus groups was Lupe Morales, the fictional Latina grandmother pictured above. Participants raved over Lupe. Of course, Lupe as a messenger cannot be separated out from the message she shared, about her granddaughter opening her eyes to the issues with using animals for food. This heartwarming story used the younger generations stereotype against itself, to great effect:

I felt more connected to this on a personal level just because I think about my kids and like the earth that they're going to inherit. So, when she said ‘I want her to live on a healthier planet,’ that's also something that I hold valuable for my own children.

Liberal woman, 29

I mean, I always like any type of education or advertisement with storytelling like this, and you're showing somebody that was older and that they would have never thought about not eating meat because that's how they were raised and how they're open to these kinds of changes.

Moderate woman, 65

I like that the granddaughter is the one who's educating. You always have a sweet spot for your grandmother, so it's nice to see.

Liberal woman, 30

I think this has a good point. My daughter has taught me a lot about how to eat better. You know, because for us, we just did what our parents did. So I think that if the younger generation can come in and teach the older ones, I think it's a good thing.

Progressive woman, 58

Money Undermines Credibility

A common concern had to do with the motivations of whoever was behind the ballot measure. Participants suggested they would lose faith if it turned out the measure was being pushed by monied interests.

I would want to know if this particular initiative is being funded by someone who has a financial interest in people consuming less meat. It would be useful in figuring out their motives.

Liberal man, 31

Participants were also sensitive to rich people, including celebrities, telling them what to do. Especially in light of the common view that eating vegan is expensive, celebrities who did not specifically discuss the affordability of animal-free food were sometimes accused of hypocrisy.

I hear a lot of celebrities, like, ‘oh, yeah, I'm vegan. And I also drive an electric car. And I have a mini private jet instead of a private jet.’ And it's like, okay, because you can afford to do that. Good for you. But yeah, a lot of us just don't have the ability to live that way.

Liberal woman, 23

You probably have a chef. That's how you're able to leave meat behind.

Liberal woman, 45

These patterns undermined two categories of messengers we tested: celebrities and entrepreneurs.

We thought that entrepreneurs leading pioneering animal-free food companies might make good spokespeople, representing a vanguard who have put their own time and money into making an animal-free food system a reality. But people broadly considered them to have too much of a conflict of interest to be trustworthy:

The end goal I may agree with, but the speaker, their motives don't sit well with me.

Progressive man, 29

This statement makes it look like it's entirely about the money. And the whole end goal and the whole message is irrelevant at this point.

Liberal man, 24

Money is what motivates people here, it's people's margins that they care about… I feel like this is just a very American statement. ‘We will do this thing. It will make me money. Yeah, the random end result is that the environment’s better and people are healthier, but I'm still making money.’

Liberal woman, 28

We recommend against elevating investors and entrepreneurs as spokespeople to the general public, though they may appeal more to conservatives.

Meanwhile, we recommend there is a role for celebrity messengers, but they should use caution to avoid being seen as hypocrites. Celebrities are probably an exception to the efficacy of the meat-eating messenger: a rich meat-eating spokesperson would likely be labeled a hypocrite. When appropriate, celebrity advocates should name the affordability and accessibility of meat alternatives as a key issue and present a solution. In doing so, they can be recast as self-aware and down to earth.

“Activists” Are Ineffective

Care should be taken to present messengers in a role other than activists. Behavior associated with “activists” (e.g. protesting) is often necessary to draw attention to a message, but the messengers should never refer to themselves as activists and should subvert activist stereotypes in their dress and speech.

Relatable Photos

Participants responded more favorably to photos of messengers whose eyes were clearly visible. This means faces should be well-lit, photo resolution must be high, and the speaker should be facing the camera, ideally wearing a friendly smile.

For some messages, feeling connected with the messenger is relatively unimportant. For instance, a message about the cognition of animals is more about animals than the animal behavior expert giving the message; animals are the central character. But the meat-eating messenger is the central character in the story they share. A clear photo of a friendly-looking person strengthens those messages, even when the tone of the message doesn’t necessarily seem friendly.

Consider the images below. We chose the image on the left because it was a real photo of an advocate. We applied simple filters to brighten it (center), but it still elicited a significantly less positive reaction than the photo on the right. (Other differences between the photos may also have contributed.)

There are times when advocates may wish to use a photo of a messenger in action, where photographic conditions were not ideal. We stress the importance of professional-quality photography in these situations.

Note that we have not followed our own advice in some of the images shown later in this report. We believe many of those slides would be strengthened with better photographs.

3.5 Recommendation: The Anatomy of a Persuasive Message

Overall, we recommend advocates include as many of these components as possible in their public-facing messages:

- Information about the messenger that makes them relatable or credible to the listener.

- Images or language discretely highlighting the emotional relevance of the topic to the listener, in a way that leaves room for them to make the connection themselves.

- An accurate, non-exaggerated factual claim, ideally involving a number or statistic.

- A citation of the statistical claim, such as a link for further reading.

- Framing language explicitly or implicitly describing society evolving together beyond using animals for food.

- Empathy, validation, or another strategy (as discussed in the previous report in this series) to preempt common objections.

All these components can be stitched together into a story. In turn, that story can convey one of many narratives that have the potential to undermine the dominant narratives in favor of using animals for food.

4. Proposed Counter-Narratives for Animal Freedom

The ultimate goal of this study was to identify narratives that could most effectively build support for the goals of animal advocates. All of the recommendations discussed so far were developed in tandem with these new narratives. This section examines the narratives themselves, providing examples of how our other recommendations can be incorporated.

First, what exactly do we mean by narrative? For the purposes of this report, we borrow the definition posed by the FrameWorks Institute: “Narratives are patterns of meaning that cut across and tie together specific stories. They are common patterns that both emerge from a set of stories and provide templates for specific stories.” In other words, while stories have specific characters, scenery, and events, narrative arises when those unique elements in different stories share essential qualities. For instance, the bootstraps narrative tells a story of an enterprising person achieving success through their own effort after starting with nothing. According to FrameWorks, “Scholarship across disciplines has identified a set of specific benefits of narrative—effects that narratives are distinctively capable of producing, in comparison to other types of frames…”

Here we present the narratives we most recommend, along with ways to improve narratives already popular among advocates.

4.1 Standout Narratives

We recommend using the following narratives in public-facing communications based on their strong performance across the board.

Consumer-Voter Conversion

- Character(s): A highly relatable "average Joe" meat-eater, especially from demographics not typically associated with veganism and animal rights.

- Plot: The main character experiences a shift in perspective from thinking of veganism as an ineffective or unnecessary consumer action, to thinking of animal freedom as a necessary social evolution.

- Point of View: Average meat-eaters (the audience’s own point of view).

- Values: Collective action for a bright future; responsible stewardship of the planet.

- Key words/phrases: right direction

A central theme of this study is how animal advocates can switch from engaging with the public as consumers to engaging with them as voters. That transformation is the central plot point of the consumer-voter conversion narrative.

This narrative essentially tries to cast the listener in the central role. The goal is to use statements that most people could imagine making themselves, and a messenger they can relate to.

Presenting this shift in perspective as a story provides useful subtlety. We tested a more direct message contrasting consumers and voters which did not perform as well:

When this message came from a meat-eating messenger who was describing their own personal conversion, it was much more effective.

“Humane” Deception

- Character(s): Deceptive marketers; the public.

- Plot: The secret gets out that “humane” meat is just a deceptive marketing ploy.

- Setting: Day-to-day life, a factory farm, or a sanctuary

- Point of View: Average meat-eaters (the audience’s own point of view).

- Values: Being informed (as opposed to ignorance)

- Key words/phrases: it’s no secret; no humane way

The animal messenger images shown earlier also portray this narrative.

Our participants held a range of views about welfare labels. Some found them trustworthy and felt comforted buying products with high welfare labels. Others considered these labels to be a sham, stating that they don’t mean much. Still others had never thought about common welfare labels or had scarcely even heard terms like “cage-free” and “free range”.

The humane deception narrative establishes the second view as the common sense view by asserting that it is “no secret” that these labels are deceptive. We first tested the phrase “everyone knows” (borrowed from a participant) but people who didn’t know found it off-putting. “No secret” performed better, perhaps because it was more inviting while still establishing that skepticism of humane labels is the norm.

We recommend pairing humane deception with a meat-eating messenger because trustworthiness is key for this narrative. As with many other issues, people have heard conflicting information about animal welfare and they don’t know what to believe. An ordinary meat-eating peer is least likely to be seen as having ulterior motives.

We also recommend supporting humane deception with facts about the impossibility of scaling low-density animal agriculture. Because people are sensitive to the cost of animal-free food, advocates can take this opportunity to emphasize the dramatic cost increases inherent to farming animals this way.

Open Your Heart

- Character(s): A person of moral leadership

- Plot: We have all been shutting off our emotions and ignoring our moral instincts, but now we have a chance to correct that mistake.

- Values: Compassion

- Key words/phrases: heart; disgust

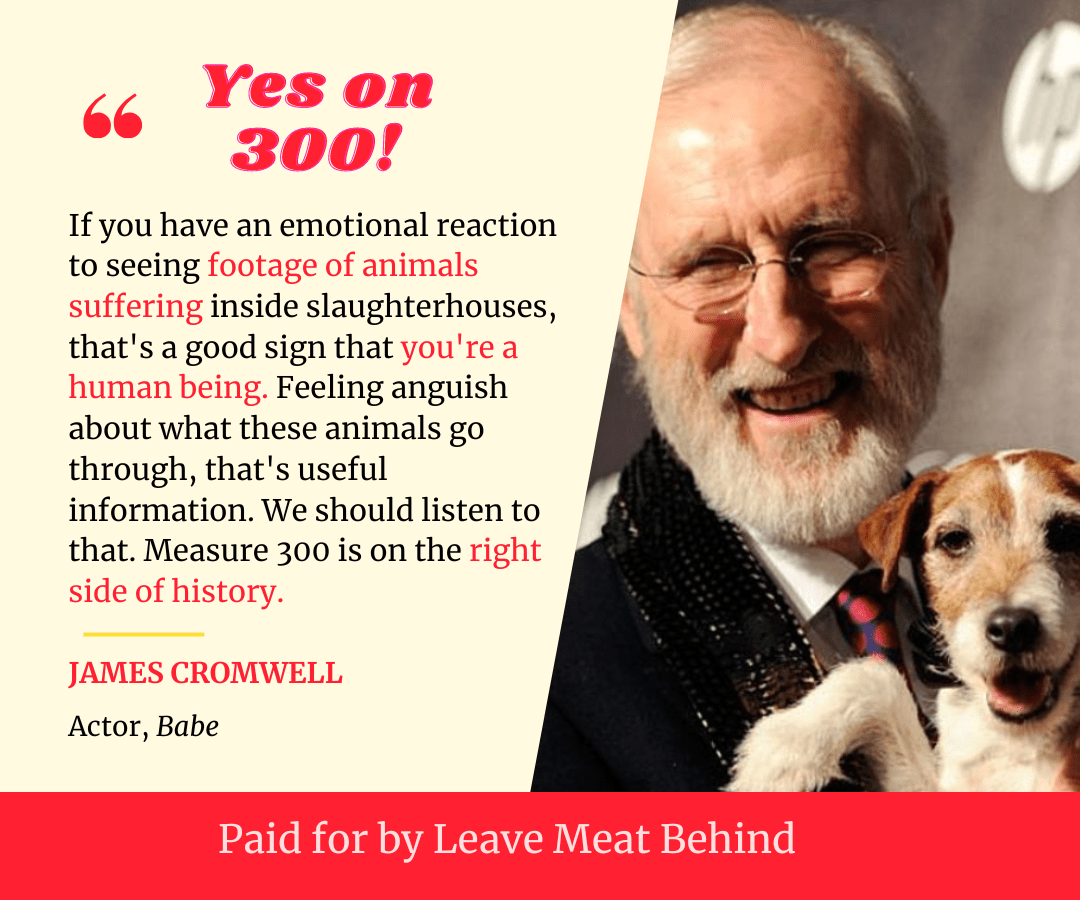

This message relies on the moral authority of the messenger, as perceived by the intended audience. An ordinary peer is not ideal here. We limited the celebrity messengers we tested to those who would plausibly say something supportive of animal freedom. James Cromwell is associated with film roles that portray positive moral role models, and he was warmly received by most of our participants as a moral messenger:

I just love James Cromwell so this is very effective for me.

Progressive woman, 71

As we discussed earlier, however, wealthy celebrity messengers are vulnerable to being seen as hypocrites if they do not explicitly address the issue of affordability. We believe this narrative will be strongest coming from whatever messenger has the greatest moral credibility among the target audience.

Trailblazing a Better Way

- Character(s): Scientists, farmers, and other food system innovators

- Plot: An visionary innovator shows that an animal-free food system is possible.

- Setting: Animal product alternative lab, transitioning farm, etc.

- Point of View: A visionary person who can clearly see a brighter future

- Values: Innovation, modernism, equity, optimism

A particularly strong version of this message not pictured here involved a researcher explaining the process of precision fermentation to produce animal-free dairy. We found that skillful explanations of scientific processes activated the positive modernity frame and generated excitement about the transition to animal-free food. We recommend messages explaining the science behind these alternatives using the trailblazing narrative.

Participants specifically appreciated the strong optimism of this narrative. However, advocates must be aware of the public’s distrust of messengers with a financial interest. Our restaurant owner did not receive this backlash, but meat alternative entrepreneurs did. Where possible, scientists, farmers, and others who aren’t thought of as being financially motivated make the best trailblazers.

Another concern raised by many participants was whether the transition to an animal-free food system would be done equitably, or if it would replicate current social injustices. We recommend trailblazers name social equity as one of their central motivations, and where appropriate, describe how their approach will reduce inequality.

Stuck in the Past

- Character(s): Reactionary animal farmers

- Plot: Someone who grew up on a farm or around farmers rejects the farmer legacy argument

- Setting: Rural area (perhaps where the economy is being revitalized by a modern industry)

- Point of View: A former animal farmer or child of farmers who has left the industry

- Values: modernity, rationality

In the previous report, we discussed how the farmer legacy narrative often presented by animal farmers and journalists was unpopular among our participants. This narrative relies on the weakness of that opposition message.

We did not test the stuck in the past narrative using social media-type stimuli, but this is an excerpt of the text we used for a survey experiment:

Barney Lewis, who came from four generations of cattle ranchers, isn’t who you might think of as a typical advocate. “A lot of my neighbors are still clinging to this worn out image of the heroic family farmer struggling to make a living off the land,” Lewis explained to a curious local. “But that just ain’t how it happens anymore. Everything’s gotten big. Some people still call themselves ‘family farmers’ when they have a multimillion dollar operation with 10,000 cows packed into a tiny feedlot. Other farmers are genuinely struggling, but it’s because they’re trapped in a cycle of endless debt to Purdue or Tyson. For those folks, switching to crops can be a way to escape that cycle.”

Fictional example of the "Stuck in the Past" narrative

4.2 Refining Other Popular Narratives

Reactions to these narratives were more complicated than those above. Because similar narratives are already in use by advocates, we offer suggestions for how they can be improved.

Level the Playing Field

- Character(s): Corrupt government and corporate officials engaging in backroom deals; an underdog calling for more fairness in the food system.

- Plot: Crooked corporations conspire with politicians to get an unfair advantage from subsidies, but now voters can correct the balance to help a benevolent underdog.

- Setting: Government, halls of power.

- Point of View: Inside the system (trying to change it from within)

- Values: Fair competition, especially in business; aligning responsibility with affordability.

- Key words/phrases: level the playing field; responsible/affordable; food deserts

Information about massive federal subsidies to animal agriculture is an effective way to disrupt the consumer frame, because it highlights the role the government already plays in consumer behavior. But subsidies are a complicated topic; even economists cannot nail down the true value of subsidies to the meat and dairy industry.

The level the playing field narrative is a way to simplify the topic. A level playing field is an explanatory metaphor for the role that subsidies play in the food system. This narrative was a way to bypass the complicated discussion about subsidies and explain the need for government action.

Denying Natural Behaviors

- Character(s): animals, animal behavior experts

- Plot: animals used for food would have rich social lives, but modern farms deny them the ability to live natural lives

- Setting: Sanctuaries, factory farms

- Values: naturalism, respect for animals

- Key words/phrases: no humane way

Participants often stressed the importance of animals’ ability to engage in natural behaviors even while being farmed. The denying natural behaviors narrative tells stories about the natural behaviors that are impossible in modern farms. However, compared to the messages in the humane deception narrative, these messages were more likely to bring up welfarism and a desire to improve (rather than eliminate) animal farming.

We recommend focusing on animals’ desire to live (denied by the act of slaughter) over these behaviors (denied by living conditions in factory farms). When discussing natural behaviors, we recommend focusing on family and social connections, such as in the messages above.

Bloody Industry

- Character(s): A former slaughterhouse worker or contract farmer

- Plot: One worker’s experience demonstrates the inherent violence of the industry

- Point of View: human suffering inside the industry

- Values: compassion, justice/equity

In recent years, there have been increasing calls among advocates to focus more messaging on the suffering of workers inside animal agriculture industries. We tested numerous messages based on worker welfare.

The most common issue we encountered with worker-focused messages is that participants did not believe issues of worker abuse are isolated in the slaughter industry. They immediately connected such messages to larger issues in labor relations, and suggested that the solution has little to do with regulating animal agriculture specifically. This distracted from the issues animal advocates hope to focus on.

There's horrible work conditions for humans, not just in the United States, but across the world. And we're not going to go after the food industry first because of work conditions alone.

Conservative man, 23

it seems like they're conflating labor issues with animal rights issues, as if they're making the argument that there is something inherent in working in a slaughterhouse that prevents good working conditions. And I think those are separate issues.

Liberal man, 31

The key to overcoming this is to clearly emphasize the harms that are unique and inherent to working in a slaughterhouse, namely the proven psychological harms of killing all day. Even with this correction, the bloody industry narrative was not among the strongest.

Sounding the Alarm

- Character(s): A whistleblowing scientist

- Plot: A scientist urgently tries to share the message that a key driver of the climate crisis is being overlooked

- Key words/phrases: comparison to fossil fuels, green energy, and electric cars

A subset of our participants were particularly motivated by the connection between animal agriculture and climate change. But working this connection into the form of a story was difficult. One reason stories are useful is they help people remember facts, which is crucial because the public is much less aware of the environmental harms of animal ag (compared to the animal welfare-related harms).

We feel there is clearly a role for climate-centered messaging, but we believe more research is needed to find more memorable ways to package those messages.

5. Policy Demands

We also gauged participants’ reactions to various policy measures. The fictional ballot measure presented by the interviewer ranged from banning slaughterhouses in one state by 2028 or animal farming by 2035, to merely providing government subsidies to animal-free food alternatives. Here’s what we found

5.1 Radical Flank Effects

Sociologist Herbert Haines describes the positive radical flank effect as when “the bargaining position of moderates is strengthened by the presence of radical groups.” We clearly observed a microcosm of the radical flank effect in our participants’ reactions to different policy demands.

The first round of focus groups were presented with a ballot measure to end the operation of slaughterhouses in one state by 2028. Participants agreed this was far too extreme and proposed more moderate solutions: a slower timeline, or a sin tax on meat.

In the next round, the timeline was more than doubled, to 2035. Again, participants felt this was too extreme, so we changed the proposal for the next round to a meat tax paying for a meat-alternative subsidy. In the absence of a slaughterhouse ban, participants found this proposal far too extreme. Even after we eliminated the tax completely, participants described it as “going from zero to 100.” They suggested a simple public education program instead.

For most participants, while they may have mixed feelings about meat, any negative feelings are more than overridden by negative feelings toward change. While the right messages can help a great deal, our interviews suggest that ultimately, advocates will be dragging the public along if any meaningful change is to occur.

We recommend the animal movement should capitalize on this particular radical flank effect. Whatever policy objectives the movement wishes to enact in the short term, we should ensure that significantly more ambitious proposals are in the public’s awareness and are even being actively pursued by a credible radical element. Our findings suggest that from a public opinion perspective, the radical flank has a vital role to play in building acceptance for the movement’s short-term goals.

Note that this recommendation does not necessarily have to do with radical methods, only with radical policy demands. The animal movement’s radical flank does not necessarily need to throw molotov cocktails (or even cans of soup) to make moderate demands seem reasonable. Using compassionate messages and working within the bounds of the law to advance a meat ban on a short timeline might suffice to create the desired effect.

5.2 Nonrestrictive Policy Remedies

Our participants almost categorically preferred policy solutions which do not directly restrict choice. On one end of this spectrum, any type of ban was seen negatively. On the other end were toothless proposals like an “education program”. Between these two extremes, however, advocates should know that there could be highly impactful government programs that are not seen as directly impacting consumer choice.

The most prominent from our research is subsidizing animal-free alternatives. This idea was repeatedly generated by our participants and remained relatively popular when the interviewer presented it. Generally, the approach of trying to make animal-free food the more affordable option was seen as effective and appropriate, so much so that a reasonable number of participants even supported funding it with a meat tax.

Meat taxes alone are seen as further towards the restrictive side of the spectrum. We tested a message framing a state-level meat tax as cancelling out federal subsidies. This had some success, but we anticipate it would be difficult to make this connection outside of such a long-form conversation.

Participants also repeatedly generated a proposal for the government to help animal farmers transition. This proposal was very strong from a messaging standpoint. We recommend advocates further investigate policy goals that could fit this description.

5.3 Affordability is an Opportunity

One of the most pervasive objections in this round of research had to do with the affordability of animal-free food. Many participants saw the price of animal-free food alternatives as a major obstacle to more widespread adoption. This objection proved challenging to address through any kind of reframing; veganism being expensive was a widely shared belief that was confirmed by participants’ own experiences at the grocery store.

If this cost cannot be addressed through clever messaging, it still presents advocates with an opportunity. By focusing their political objectives on the price of animal-free foods, advocates could turn a major objection into a point of cohesion with the broader public. Messengers advocating for government money to make animal-free foods more affordable and accessible were seen favorably by our participants.

We recommend advocates consider policy demands focused on decreasing the cost of animal-free foods. At the least, including such measures in a broader package will help the public see that animal advocates are in touch with the concerns of ordinary people.

6. Conclusion

In the previous phase of the study, we uncovered numerous insights into how the public thinks about animals used for food. The goal of this phase was to design persuasive messages based on those insights. Through over 60 hours of feedback from ordinary meat eaters, we refined the tone, messengers, and narratives of these messages into recommendations that can benefit any public-facing animal advocacy. Some recommendations (such as those around animal messengers and the humane deception narrative) refine messaging strategies already in wide use, while others (like meat-eating messengers and the consumer-voter conversion) open up entirely new strategies.

Compared to the previous phase, part of our goal was to more closely approximate the way people usually encounter animal advocate messages. Extended conversations are important but they are a rare opportunity; a great deal of our interaction with the public comes in social media ads or short quotes in news stories. If the design of these focus groups was a step in that direction, the ongoing stages of this study go even further using survey experiments.